President Yoweri Museveni’s decision on August 3 to remove all health staff at Nakawuka Health Centre in Mpumudde village, Wakiso district over alleged poor service delivery is once again shinning a spotlight on a dark part of the sector, writes The Independent Team.

The President acted against the 14 staff after arriving unexpectedly at the centre at 10am and finding no staff on duty. He waited for two hours before the first health worker arrived and others trickled in. Later, at an impromptu baraaza community meeting, residents complained that the health workers are never at the clinic, are rude, and rarely provide drugs whenever they are around.

Based on the pile up of absenteeism and the complaints by residents, the President ordered the Minister of Health to remove workers from the facility. It is the latest action the President is taking as his way of signaling his seriousness on Hakuna Mchezo, the name for his campaign of getting tough on service delivery.

After a day without staff, the rural clinic is now being manned by medical staff from the army and has been the epicenter of activity of all top Ministry of Health staff, including the minister; Ruth Aceng.

Residents who spoke to journalists said the President’s intervention has improved the quality of service. The question, however, is whether such random intervention is sustainable since Uganda has over 3,000 government-owned health facilities of different levels and the President cannot visit each of them. Experts say what is needed is a system-wide overhaul to ensure that service delivery improves.

According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) figures, currently, less than 2% of all people who fall sick attend the Out-patients sections of public health facilities. Most visit private clinics instead.

People who reject government health facilities cite the same reasons as those given to Museveni by residents of Mpumudde village.

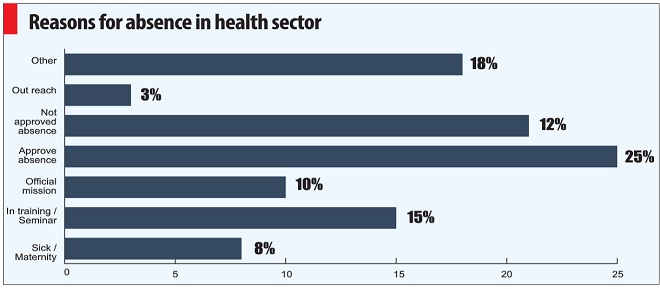

Mainly, they say, the health workers will either arrive late or not at all, will attend to only a few people and not provide adequate or proper diagnosis, will be rude, and will not provide prescribed drugs.

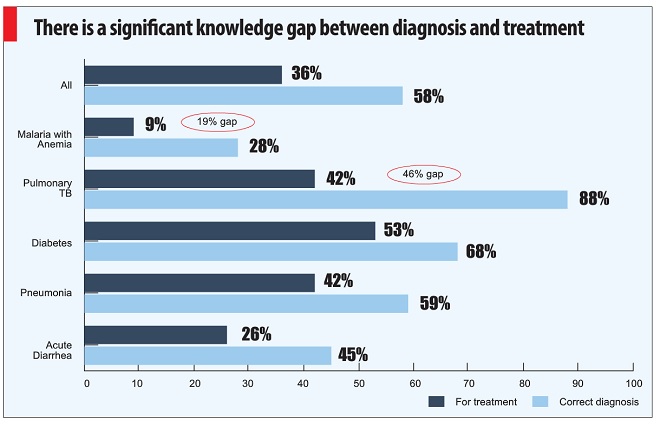

These claims by patients are a carbon copy of findings narrated in a report titled `Education and Health Services in Uganda: Data for Results and Accountability’ by the World Bank and the African Economic Research Consortium.

Museveni needs to first read this report by the World Bank on Uganda

Released in November 2013, the report noted that although Uganda’s health sector has achieved a lot in recent years, including in under-five mortality falling by half from 180 to 90 deaths per 1,000 live births between 1989 and 2011, the improvement are a result of “vertical Programs”, mainly donor-funded projects that target one disease or health issue.

The report noted that areas like, the death of women from pregnancy related causes that require government-led “horizontal programs” that should be coordinated and system-wide have either stagnated or slightly deteriorated.

“These disappointing results are most likely related to the quality of service delivery,” the report noted.

It notes that a combination of basic elements is required for quality services to be delivered at the frontline and lists adequate financing, infrastructure, human resources, material, and equipment. It adds that “institutions and governance structure must provide incentives for service providers to perform.”

“The impact of financial and material resources is substantially reduced when frontline providers face a set of incentives that are not conducive to performance,” it says, “Therefore; simply increasing the level of resources is not enough to address the quality deficit.”

Heavy workloads?

Surprisingly, although Ugandan health workers often complain of heavy workloads and poor pay, the World Bank report notes that their situation is not very different from other African countries.

Patient caseload, as the average number of outpatients that a health provider attends to per working day is 6.1 in Uganda which is a “surprisingly low number”, according to the World Bank report.

Smaller facilities that are staffed with one or two health providers had the largest caseload with 11 outpatients per provider per day. But middle-level facilities like Nakawuka, which have three or more staff, attend to between 5 and 6 patients per provider per day – meaning they are attend to 25 to 30 patients a day. Those in bigger facilities of over 20 health providers record a caseload of only 2 outpatients per provider a day.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price