Nakawuka Health Centre is a typical level III rural facility, with its derelict single-storey block of grey rough-cast walls and fading red iron roof, a decaying colonial-style residence and outhouse for staff, and unkempt grounds. But it is most likely far better off than many rural health centres around the country.

This is partly because Wakiso district where it is found is among the better served areas in Uganda. It has the highest number of health facilities, 109, after Kampala, according to UBOS. Mukono district has 45 facilities, Kole district 11 and Amudat just 9 facilities. That means conditions in the north and northeastern Uganda are far worse than what President Museveni saw in Mpumudde.

Typically, level III health facilities of the Nakawuka type are also not the most poorly staffed. That prize goes to the lower Health Centre IIs and the Urban Area Health Units that can have up to 70% of approved staff positions unfilled.

Absenteeism

In such a situation, the lack of job commitment or; as the World Bank report calls it, the “low service provider effort” exhibited by Ugandan medical workers cannot be blamed on heavy workload. The World Bank report blames it on absenteeism.

The reports notes that health providers, like workers everywhere, are expected to sometimes be absent for any number of reasons. It notes that a typical expected absence rate is about 5 to 10 percent on authorized leave. It notes that the rates in Uganda which are 25% for approved leave and 52% if other reasons are included “are substantially higher”.

The researchers found that almost half (46%) of staff were not on the facility premises during the research visit. The absenteeism cuts across all cadres, from the top doctor to bottom nurse. It also found that health workers in rural areas are more likely to be absent than their urban counterparts. In most cases, they have legitimate reasons to be absent; such as attending training or a seminar, or on official mission and other approved absence.

But, according to the World Bank report, from the citizen’s perspective, if almost half of staff is not attending patients there is a legitimate reason for concern even if every single absence was sanctioned.

“Better management at the facility or higher administrative level could probably curb sanctioned absence by implementing tighter leave rules,” it notes.

“The problem of low provider effort is largely a reflection of suboptimal management of human resources.”

For evidence, it says it found that more than half (52%) of public health providers were not present in the facility and 60% of this absence was approved, and “hence potentially within management’s power to influence”.

Compared to public health facilities, according to the researchers, the private facilities, are better when it comes to mothers’ and children drugs, equipment, and infrastructure.

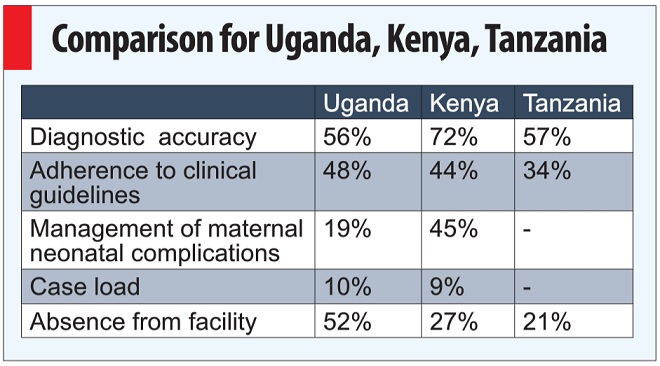

When the researchers compared Uganda to Kenya, Tanzania, and Senegal, they found Uganda performed better than Kenya on input indicators and adherence to guidelines.

However, Kenyan health providers were 20 percent more likely to get the diagnosis right and were twice as likely to correctly manage maternal and neonatal complications.

Uganda has only a slightly higher caseload than Kenya of 10 patients versus nine patients, according to the research but “Kenya’s public providers seemed to exert a higher level of effort because of the very high absenteeism rate observed in Uganda”.

The report noted that basic inputs and infrastructure—with the notable exception of drugs — are also largely available at Ugandan health facilities. Focus, therefore, has to be paid to the level of knowledge and effort put into service delivery by health workers.

It found that only 44% of the public health facilities had all six of Uganda’s essential drugs. The adequate availability of priority drugs for mothers and children remains a challenge with only 39% and 23% respectively available in public facilities.

Within the public sector, rural health facilities had poorer equipment and infrastructure, although availability of assessed drugs was higher in rural facilities.

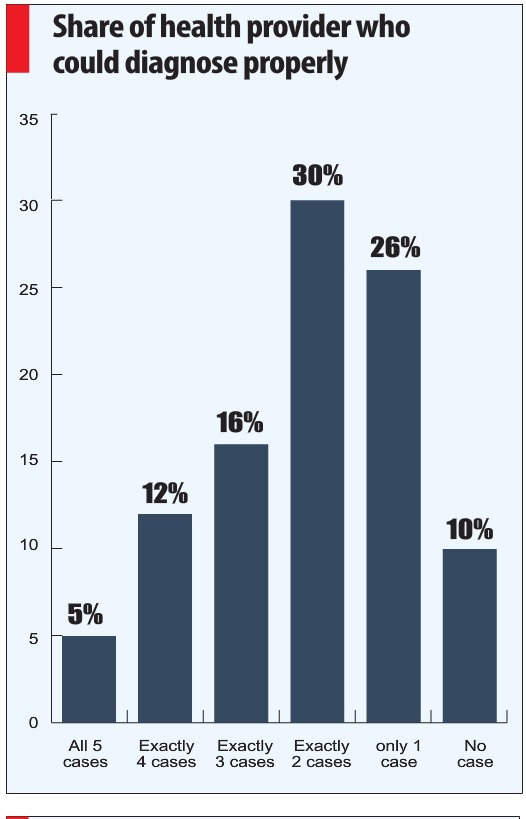

However, the low level of knowledge was a big concern. Only 35% of public health providers could correctly diagnose at least 4 out of 5 very common conditions (like diarrhea with dehydration and malaria with anemia). In health centers that only offer outpatient services (HC2), half (49%) of the providers could not identify more than one of these conditions. “Worryingly, public health providers followed only one out of five (20%) of the correct actions needed to manage maternal and neonatal complications,” the report noted.

*******

Some suggestions to improve attitudes of health workers

- Client handling trainings to reinforce positive attitudes and reduce negative ones. Regular support supervision sessions to encourage respectful handling of patients.

- Solving the root causes such as inadequate staffing, poor remuneration and lack of adequate supplies.

- Recruiting and training health workers who have an intrinsic desire to help the sick.

From `Who is to blame for the Poor Health Workers Attitudes and how can we cure This Disease?’ an article by Dr. Elizabeth Ekirapa-Kiracho on the Knowledge Translation Network Africa website

****

editor@independent.co.ug

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price