Kampala, Uganda | THE INDEPENDENT | Special needs schools have remained closed, despite a go-ahead given to them by the Ministry of Education, to resume operations for all learners, four months ago.

Education authorities gave a green light to schools in the said category and their international counterparts to reopen at full capacity, at the time the gates were reopened for candidate classes. The decision was based on an assumption that the schools have a limited number of students and would not find challenges in enforcing the standard operating procedures.

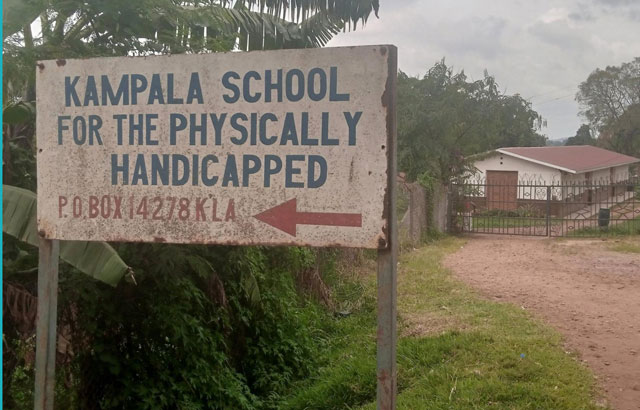

But Esther Margaret Kiwanuka, the headteacher of Kampala School of the Physically Handicapped children, shares that although they have a total population of 160 learners, they find it difficult to manage them in the wake of the COVID-19 restrictions.

Kiwanuka points out that social distancing is critical yet impossible for special needs children, a number of whom are cared for by peers and caretakers on a one-to-one approach. She notes that they need special guidelines tailored to fit their institutional needs if they are to operate at full capacity.

She adds that even if they had decided to adhere to the given procedures, the available space wouldn’t be enough because they need to procure more infrastructure-which are disability friendly- and more staff, which comes at a huge cost. Kiwanuka adds that the proposal for learners to study in shifts might also not be possible for special needs schools because many adopted a boarding setting.

A staff member at Wakiso school for the deaf also noted that the school was only able to recall S.4, S.5, and S.6 students given the available space. “Unlike other learners, ours cannot wear masks as recommended. This means that social distance can not be compromised, yet the only available space could only cater for a few students,” the staff member said.

Pius Okecho, the headteacher of Mulago School of the Deaf, explains that they are considering to buy tents as an alternative and utilize the classrooms for dormitories in case that the government resolves to reopen schools for non-candidates. He notes that the total population of 200 learners in the school cannot be accommodated in the structures available and they can only improvise.

Okecho adds that they are finding it hard to feed the 38 candidates they have currently because many of their parents are also struggling financially. Oketcho is concerned that the situation could worsen with the recall of non-candidate learners.

Approximately 2.5 million children in Uganda live with some form of disability, according to an assessment by UNICEF. These include learners with muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, down syndrome, autism, dyslexia, processing disorders, bipolar, oppositional defiant disorder, the visually impaired, and those with hearing impairments.

But these children have already been left out in all forms of continuos learning that were arranged by the government as they were seen to be ‘outright damaging for many students with disabilities who require a strong, close-knit network of people supporting their often multiple and complex needs.’

Sarah Bugoosi Kibooli, the Commissioner in Charge of Special Needs Education, says that the department is discussing how best the differently gifted learners can study.

“We are going back to the drawing board to look into the matter at hand. There are some things that we saw during the recent school inspection. We also collected some recommendations from the schools which can be discussed to forge a way forward,” Bugoosi says.

Records show about 10 per cent of children with disabilities can access education through special schools with five per cent going through Inclusive Schools.

********

URN

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price