Slippery slope: the more we lie, the easier it gets

Paris, France | AFP |

Whether cheating on taxes or one’s lover, the little lies we tell can quickly escalate into big ones, according to a study released Monday that describes dishonesty as a “slippery slope”.

Serial untruths, moreover, register a diminishing emotional response in the brain, researchers reported in Nature Neuroscience.

Indeed, the biochemical link is so strong that scientists could accurately predict in experiments how big a lie someone was about to tell just by looking at the brain scan of their previous prevarications.

“This study is the first empirical evidence that dishonest behaviour escalates when it is repeated,” said lead author Neil Garret, a researcher in the Department of Experimental Psychology at University College London.

Understanding how people graduate from white lies to whoppers despite the social norms or morals that discourage mendacity is of more than academic interest, the authors argue.

Whether it is “infidelity, doping in sports, making up data in science, or financial fraud, the deceivers often recall that small acts of dishonesty snowballed over time,” noted co-author Tali Sharot, also of University College London.

“They suddenly found themselves committing quite large crimes.”

In the experiments, some 80 volunteers were asked to individually assess high-resolution photos of glass jars filled with different amounts of pennies.

Then, via a computer, they were instructed to advise a remote partner looking at a poor-quality image of the same jar as to how much money it contained.

These partners were in fact actors working with the scientists, but the volunteers did not know that.

In the first test, the volunteers were given an incentive to be honest.

“They were told that the more accurate their partner’s estimate, the more money they would both receive,” Garrett explained in a press briefing.

This set a benchmark for other scenarios in which volunteers were given an incentive to lie.

In one experiment, a deliberate falsehood resulted in gains for both advisor and advised. In another, the volunteer understood that a self-interested lie would come at the expense of the partner.

Practice makes perfect

“People lie the most when it is good for them and for the other person,” said Sharot.

“When it is only good for them, but hurts someone else, they lie less.”

Participants differed sharply on how far they wandered from the truth, and the rate at which their dishonesty escalated.

And those identified beforehand in questionnaires as less forthright were also more likely to lie during the experiment.

But most volunteers not only easily slipped into a pattern of dissembling; they also ramped up the intensity of their lies over time.

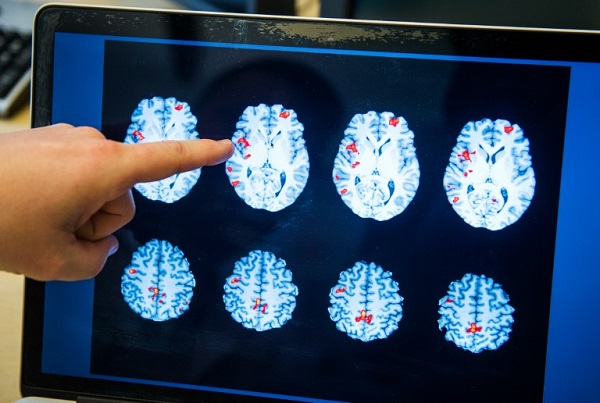

Twenty-five of the participants underwent functional MRIs — brain scans — during the experiments.

The part of the brain that processes emotions, the amygdala, responded strongly when lying occurred.

At least it did so at first.

But even as the lies grew bolder, the amygdala lit up less and less, a process the researchers called “emotional adaptation.”

“The first time you cheat on your taxes, for example, you might feel quite bad about it,” Sharot said. “That bad feeling curbs your dishonesty.”

“But the next time you cheat, you have already adapted, and there is less of a negative reaction to hold you back.”

Whether the reduced activity in the brain’s emotional command centre helped drive the slide towards dishonesty, or was simply a reflection of it, remains unclear.

But one conclusion from the study does seem inescapable: the more you lie, the better you get at it.

“If emotional arousal goes down, it is possible that people are less likely to catch you in a lie,” said Sharot.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price