The beloved Virika Cathedral—an architectural and historical landmark that had stood for nearly six decades—collapsed, reducing to rubble a sacred space where thousands had gathered in prayer over the years.

Kampala, Uganda | CHRISTOPHER KISEKKA & WILSON AKIIKI KAIJA – URN | Fifty-nine years ago on March 20, a powerful earthquake shook Uganda’s Tooro region, sending tremors across Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

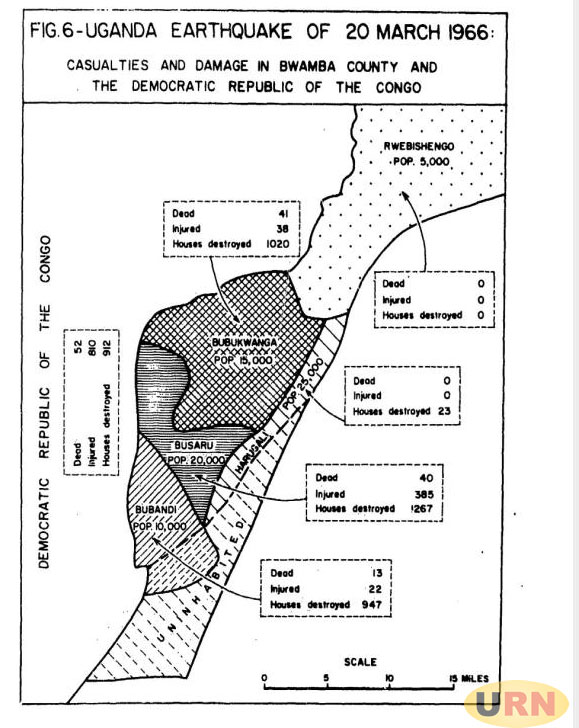

Records indicate that the destructive earthquake, in the early hours of Sunday, 20 March 1966, was officially recorded at a magnitude of 6.6 on the Richter scale, though several monitoring stations reported readings as high as 7.7. It remains the strongest earthquake ever recorded in the region to date. The earthquake was most severe near the Uganda-DRC border, with its epicentre near the town of Bundibugyo, leaving behind a trail of destruction and fear. It is claimed 157 lives, injured 1,323 people, and damaged or destroyed over 6,700 homes.

A July 1966 UNESCO report details the terrifying moments when, at around 4:45 a.m., the earthquake violently shook western Uganda, eastern Congo, northwestern Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, and western Kenya, jolting residents awake. As the ground trembled beneath them, panicked people rushed out of their homes, many struggling to stand as the intense shaking made movement difficult. Witnesses described a deep, unsettling noise, likening it to the rumbling, roaring, bumping, humming, passage of a heavy truck. Others likened the noise to thunder.

In what was classified as “Zone Five of the Disaster,” nearly everyone along the Uganda-DRC border, particularly in the Lake Albert–Lake Edward region, felt the full force of the quake. Panic spread rapidly, with people screaming, children crying, and animals shrieking in distress. The main tremor lasted up to an hour, followed by multiple aftershocks, further intensifying the fear and destruction across the region. “People reported that they were obliged to sit or lie on the ground. Most of the shops at Bundibugyo crumbled within three minutes…people shouted and lit fire everywhere. Children cried, and dogs, goats and chickens were affected.

The effect in the Democratic Republic of Congo was similar,” the report reads in part. In Tanzania, at the Kyerwa tin mines in Karagwe, Bukoba, the quake caused rock falls in abandoned mining tunnels, leading to the death of an illegal miner and injuring another. Structural damage was reported in Mubende, Mbarara, and Kisoro, with additional reports of destruction coming from as far as Yumbe, Arua and Lira in northern Uganda, Masaka, Kikagati, and Jumba in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

According to reports, the terror continued for hours after the main shock, with aftershocks persisting at regular intervals throughout the day. Strong tremors were felt daily in Bwamba and Fort Portal for weeks, with some aftershocks powerful enough to be detected as far away as Mbarara, Entebbe, and Kampala.

The most significant aftershock occurred on May 18, two months later, causing additional damage in Bwamba and Fort Portal triggering small landslides along the Rwimi River and injuring one person in Katumba. Across the border, in the DRC however, the aftershock of 18 May 1966 was nearly as deadly as the main shock of 20 March.

The UNESCO report quoted local press as saying the tremor left 90 people killed, 33 injured and 916 houses destroyed in Beni. Between 20 March, when the main earthquake shook the area, and 18 May when the last major aftershock was recorded, seismological stations in the region recorded no less than 21 tremors. Some were as high as 6.3 on the Richter scale with a depth of 33 kilometres. The U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey recorded the earthquake in 126 monitoring stations worldwide, with tremors detected as far away as Samoa, California, New Zealand, the Solomon Islands, and Alaska. The earthquake also left visible changes to the landscape.

A fault line stretching 15 to 20 kilometres from Kitumba in DRC to the Semliki River was reported, while minor landslides and rock-falls were observed in the Rwenzori Mountains. Residents near the Baranga hot springs noted increased temperatures and changes in water levels, with new hot springs forming. Same tremor, different readings

While the US Coast and Geodetic Survey recorded the magnitude of the March 1966 earthquake as 6.1 and with a depth of 36 kilometres, other observation points captured different readings. For instance, the National Observatory of Athens, Greece, recorded a magnitude of 7.7, while observation stations in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, Nairobi in Kenya, and Uppsala in Sweden captured 6.8, 6.9 and 6.9 respectively, according to the UNESCO report. The Fateful Morning

The chaotic morning was vividly captured through the eyes of those who experienced it firsthand.

Bishop Vincent McCauley of Fort Portal Diocese was in Bundibugyo, the epicenter of the quake, on an official visit. He most likely anticipated a peaceful Sunday morning Mass at a local church. However, at around 5 a.m., as records from the diocesan archives recount, he was jolted awake by the violent shaking of the earth.

As buildings crumbled around him, the air filled with cries of panic, marking the beginning of a morning of terror and destruction. As the bishop rushed outside, joined by priests from the mission station, his immediate thoughts turned to the African Sisters and the young girls in the nearby boarding school.

“The Sisters were safe as were also most of the boarders, but when the dormitory crashed to the ground six girls, who had had no time to escape, were buried under the masonry,” one account recorded. Without hesitation, the bishop, priests, and Sisters dug frantically with their bare hands, pulling the girls out just in time. They were injured, but none fatally.

With the Sisters tending to the rescued girls, Bishop McCauley and his clergy turned their attention to the wider disaster. Bundibugyo had been almost entirely reduced to rubble. Two churches – Bwamba and Busaru – the priests’ residence, the dispensary, and most school buildings had collapsed. Writing to Rome six days after the earthquake, Bishop McCauley noted that it was reckoned to be the longest and severest hitherto recorded in Africa.

Different documents and messages sent out indicate that, in Fort Portal and Bwamba, 104 people were killed, 510 injured, 200 children orphaned, 6,000 left homeless with 2,157 houses destroyed. As the tremor continued and the earth heaved, the bishop and clergy succoured the injured and anointed and comforted the dying. Cathedral Collapses

At this time, in Bundibugyo, the bishop had no idea that 75 kilometres away in Fort Portal, his cathedral – Our Lady of the Snows — had also gone down. Some parts may have remained standing but a report by structural engineers he commissioned to assess the damage was grim. The cathedral plus the adjacent buildings were written off. The beloved Virika Cathedral—an architectural and historical landmark that had stood for nearly six decades—collapsed, reducing to rubble a sacred space where thousands had gathered in prayer over the years.

In the aftermath, a new earthquake-resistant cathedral was constructed, ensuring greater resilience against future tremors. Early this month, it was rededicated after undergoing its third major renovation, standing as a testament to both faith and perseverance. Uganda’s Seismic History

Uganda and the surrounding Great Rift Valley region have long been seismically active, with recorded occurrences of earthquakes dating back to 1897.

*****

RELATED STORY

*****

The Rwenzori Mountains in particular experience frequent tremors, with studies between 2006 and 2007 recording 800 seismic events per month. The Uganda Geological Survey and Mines Department captured earthquake records in the country from 1907 to 1942, a compilation of reports from 782 localities. The report lists at least 588 felt shocks in Uganda, 518 of which came from Fort Portal.

Another report, compiled in 1939 by the Uganda Geological Survey and Mines, shows that between 1925 and 1936, at least 362 tremors were recorded around Fort Portal. This number, in comparison to other areas such as Mubende which recorded 55 tremors, 46 in Mbarara, 36 in Masindi, 30 in Hoima, 23 in Entebbe, 13 in Butiaba, 10 in Kabale, seven in Masaka and six in Kampala among others.

Of the 16 more notable earthquakes felt in Uganda during this period (1925 – 1936), 12 had their epicentre in Tooro while three were around Lake Albert, a few kilometres north. Among Uganda’s most destructive earthquakes was the February 5, 1994, Kabarole earthquake, which measured 6.2 on the Richter scale and caused significant damage. Locals note that major earthquakes tend to occur in the region roughly every 30 years, with the 1966 and 1994 quakes followed by more recent tremors in eastern DRC in 2024. According to a news report by The Independent, experts warn that an earthquake can strike Uganda at any time.

They explain that earthquakes are frequent in the region, though most are too small to be noticed. While minor tremors may cause the ground to shake and household items to rattle or fall, they rarely result in significant damage. However, a major earthquake occurred on September 10, 2016, registering a magnitude of 5.7 on the Richter scale. It impacted Uganda and other countries in the Lake Victoria Basin region, with Rakai being the hardest-hit area in Uganda. The disaster left four people dead, 20 hospitalized with injuries, and affected nearly 590 people, destroying numerous homes. A Lasting Impact

The 1966 earthquake remains one of the deadliest in East African history. With a population of 8 million at the time, the loss of 157 lives was a tragedy that served as a stark reminder of the region’s vulnerability to seismic activity and the need for better earthquake preparedness. Even decades later, the memory of that devastating morning lingers in the minds of survivors and the history books of East Africa.

******

RELATED STORY

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price