Why the recent state brutality towards opposition politicians and journalists should make us revisit liberal traditions

THE LAST WORD | ANDREW MWENDA | The 19th century cartoon character, pot-bellied bourgeoisie Monsieur Prudhomme, carried a large sword with a double intent: primarily to defend the republic against it enemies, and secondarily, to attack it should it stray from its course. In the same manner my professional work as a political commentator has always had two purposes: one, to defend the cause of liberty, freedom and democracy; and two, to attack pseudo democrats who claim to fight for these ideals in their reckless pursuit of power.

Thus, while I condemn in the strongest terms the brutal arrest and torture of opposition politicians by state security forces, I am also constantly conscious of the fascist tendencies of some opposition politicians. This is most manifest among their most passionate supporters; especially online where they employ cyber bullying – blackmail, lies and slander – as a political strategy. In sympathizing with individuals whose rights and freedoms have been violated, we should not be blind to the danger these people pause to liberty and freedom in our country.

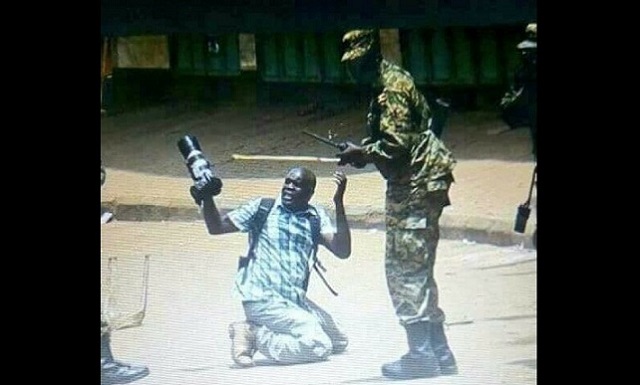

I share the sentiments of many Ugandans about the recent brutality of the security forces against unarmed and defenseless citizens of our republic. This is even more compelling; especially watching videos of security forces arresting and beating my fellow journalists. There seems to be a collapse in the moral compass of our security services. Yet discipline in the security services had, even with one thousand and one weaknesses, been the cornerstone of President Yoweri Museveni’s government and politics.

As already noted, while the actions of the state are indefensible, the behavior of opposition leaders and many of their supporters is equally reprehensible. Political and civic leaders of Uganda should encourage people to protest peacefully. Opposition politicians should get better organised to ensure they have control over their supporters who protest. When protestors are not organised, they act like a mob. Mobs don’t build things; they destroy them. This is especially so when they take the law into their hands. And once this happens, it invites and justifies harsh state response.

Therefore, I am very conscious of the fact that in the midst of public anger caused by the brutal actions of the state, most people will be inclined to ignore the provocations that led to it, like the pelting of the president’s convoy with stones, an act that I strongly disagree with and condemn. There is no justification whatsoever for citizens, however angry, to throw stones at the president’s convoy. Ugandan pundits, civil society and social media activists and journalists do not condemn this behavior for fear of annoying “public opinion” and also in order to win cheap popularity.

Secondly, for those who disagree with Museveni to make sense to me, they must exhibit superior values to his and demonstrate this not only in word, but also in deed. Right now the opposition have a lot of power on social media. There, they exhibit the worst forms of intolerance of divergent views. What would happen if they had command of the repressive power of the state? It is, therefore, critical that we go back to the liberal traditions and listen to one of its greatest philosophers, Karl Popper, on public opinion.

Popper was critical of the myth which attributes to the voice of the people a kind of final authority and unlimited wisdom. In the chapter on “Public Opinion and Liberal Principles,” in his book `Conjectures and Refutations’, Popper is critical of our blind and naïve faith in the ultimate commonsense rightness of the “man in the street.” He says, quite correctly, that the avoidance of the plural is telling since people are rarely univocal on any issue. There are as many opinions in as many streets as the people who live in the city.

Popper’s greatest contribution was the recognition that public opinion is very powerful. It can change governments, even despotic ones. So he cautioned that liberals “ought to regard any such power with some degree of suspicion. “Owing to its anonymity,” Popper wrote, “public opinion is an irresponsible form of power, and therefore particularly dangerous from the liberal point of view.”

“The remedy in one direction is obvious: by minimising the power of the state,” he went on, “the danger of the influence of public opinion, exerted through the agency of the state, will be reduced. But this does not secure the freedom of the individual’s behavior and thought from the direct pressure of public opinion. Here the individual needs the powerful protection of the state. These conflicting requirements can be at least met by a certain kind of tradition…”

In his essay “On Liberty”, John Stuart Mill had made this point. He argued that the biggest threat to individual liberty is not necessarily the state. Rather it is majorities that are willing to use the weight of numbers to suppress and silence minorities. It is for this reason that Mill wrote: “If all mankind minus one were of one opinion and only one person was of a contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silence that one person than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.”

Popper argues that it is easy to see the state as a constant danger, an evil, though a necessary one. But this is because for the state to fulfill its functions, it must have more power than any single private citizen or public corporation. He argues that even though people may design institutions to minimise the risk of the powers of the state being misused, that risk can never be completely eliminated.

Therefore, people have to continue to pay for the protection of the state not only in taxes but also in the form of humiliations suffered – for example at the hands of bullying officials. Since the danger of abuse of state power cannot be eliminated, Popper argued, the only thing we can hope for is not to pay too heavily for it.

This argument is consistent with the theme Popper articulated in `Open Society and its Enemies’ i.e. that our human institutions are inherently imperfect and that a perfect society is impossible to attain. Therefore, we must content ourselves with an imperfect society but that is, however, capable of infinite improvement. It is a conservative philosophy to which David Hume, Edmond Burke, Frederick Von Hayek and Michael Oakeshott would have agreed.

****

amwenda@independent.co.ug

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price