President Tshisekedi, visiting American senior advisor, discuss minerals-for-security deal

COVER STORY | IAN KATUSIIME | Finally, African countries know that unlike in his first term where they hardly mattered, U.S. President Donald Trump this time has the continent on his agenda.

Just as in his first term, President Trump has delayed naming the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, but on April 1 he named a U.S. State Department Advisor for Africa.

The appointment of Massad Boulous as U.S. State Department Advisor for Africa offered the latest clue on America’s renewed interest. The U.S. Department of State note that announced his appointment also concurrently announced that he was visiting the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda starting April 3.

The U.S. envoy starting out in East Africa seems well calculated. President Trump may have unleashed universal tariffs to reverse what he says are unfair trade practices to his country, but he is also looking to profit from some of the countries he targeted.

The Trump administration says it has prioritised advancing American interests at every given turn and the Bureau of African Affairs at the State Department has outlined three core objectives; advancing trade and commercial ties with key African states to increase U.S. and African prosperity; protecting the United States from cross-border health and security threats; and supporting key African states’ progress toward stability, citizen-responsive governance, and self-reliance.

But as everything shaping Trump’s Africa policy is commercial, East Africa seems to have caught the eye of Washington for the same reason since it is one of the fastest growing regions economically.

Boulos has no U.S. foreign policy experience and it is not clear what went on behind the scenes as Boulos met with the leaders of Rwanda, Uganda and Kenya besides the usual discussions on strengthening bilateral ties.

The three countries are longtime U.S. allies with wide ranging partnerships and business interests. Uganda’s counterterrorism efforts in Somalia are strongly backed by the U.S., especially the fight against Al Shabaab.

Kenya is home to several American companies and last year, it was designated as a Major non-NATO US ally by the Biden administration where Kenya was promised security goodies. But anything to do with Biden is anathema to Trump so the focus appears to be on DRC from which the U.S. is seeking lucrative business opportunities.

A typical U.S. Advisor for Africa in the pre-Trump geopolitical order would have to keep an eye on the civil war in Sudan, Al Shabaab in Somalia, a collapsing state in South Sudan, and Islamic insurgents taking over the Sahel region in West Africa.

For Boulos, his role as a Senior Advisor to President Trump on Arab and Middle Eastern Affairs means he has to engage in two demanding roles.

According to analysts who reacted to Boulos’ appointment, this presents a complication on what exactly the new U.S. administration wants to achieve with naming him as U.S. Advisor for Africa while also handling the Middle East portfolio that involves the war in Gaza and other conflicts in the region where the US is entangled. It is unusual for a U.S. official to hold such prominent dual roles.

The appointment of a Senior Advisor with a business background has elicited debate on whether the Trump White House has clear goals in brokering peace in some hotspots. This is unsettling for some foreign policy watchers.

“The story of Massad Boulos represents a fascinating intersection of international business, American politics, and the complex dynamics of perception versus reality in the modern political landscape,” writes Habib Al Badawi, a professor of international relations at Lebanese University in an article in The Raisina Hills.

Badawi traces the rise of Boulos, who was born in Lebanon, to his matrimonial relationship to the Trumps; his son Michael is married to Trump’s daughter Tiffany. According to NPR, he’s the second extended family member to be awarded a role, after Charles Kushner, the father-in-law of Trump’s other daughter Ivanka, was nominated as ambassador to France.

“This personal connection provided a gateway for Boulos to leverage his proximity to the Trump family into a role of political significance. Acting as an intermediary between Trump and Middle Eastern leaders, as well as courting Arab-American voters, Boulos has demonstrated an ability to translate personal relationships into political capital.”

Boulos has now further leveraged his relationship with Trump to take on the Africa docket at a time of radical disruption. Boulos got the Africa gig partly because he has business interests in a small automotive conglomerate called SCOA in Nigeria, which is the largest economy in Africa. Trump has already made it clear to the world that his foreign policy is transactional and nothing less.

Mineral interests in DRC

The DRC is no different. Although Trump slapped an 11% tariff on DRC, it appears he is looking for a way of tapping into its mineral wealth.

The largest country in sub-Saharan Africa is renowned for its large reserves of cobalt, titanium, lithium, and tantalum which are in critical demand in the U.S.

Ahead of Boulos’ visit, the U.S. State Department announced that Boulos and the team were to meet with Heads of State and business leaders “to advance efforts for durable peace in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and to promote U.S. private sector investment in the region”.

Before his arrival in the DRC, the Congolese government overturned the death sentences of three Americans who were convicted last year for their involvement in a failed coup attempt. The Americans — Marcel Malanga Malu, Tylor Thomson and Zalman Polun Benjamin — were among 37 people handed the death sentence in September, but have now been given a presidential pardon.

Malanga Malu’s father, Christian Malanga, a U.S. national of Congolese origin, was believed to have been the mastermind behind the May attacks on the presidential palace and a Tshisekedi ally’s home. He was killed when the attempted putsch was foiled.

On arrival in the DRC on April 03, Boulos met Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi in Kinshasa. The America public broadcaster, NPR, reported that the meeting occurred “amid speculation surrounding a possible minerals-for-security deal”.

“You’ve heard about a minerals agreement. We’ve reviewed the DRC’s proposal, and I’m pleased to announce that the President and I have agreed on a path forward for its development,” Bolous reportedly said, according to a statement by the Congolese government.

“I look forward to working with President Félix Tshisekedi and his team to build a deeper relationship that benefits the Congolese and American people, and to stimulate American private sector investment in the DRC, particularly in the mining sector, with the shared goal of contributing to the prosperity of both our countries,” he added.

On the security situation in the country he said only: “We want a lasting peace that affirms the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the DRC.”

Boulos is a Lebanese-American businessman and his brief is championing U.S. business interests while also trying to broker peace in the conflict in eastern DRC. Boulos has close ties to Trump and he serves in another role as Senior Advisor to Trump on Arab and Middle Eastern issues.

Boulos’ first port of call shows where his priorities lie as U.S. Advisor for Africa; a continent with 54 countries. The conflict in eastern DRC has been a major flashpoint in international politics: Rwanda has faced strong criticism and sanctions for its involvement, and the U.S. has not been spared either; one for its complicity and secondly for major American companies like Apple profiting from Congolese minerals while the country’s citizens continue to wallow in poverty and die in the endless fighting.

The meeting with DRC President Tshisekedi alongside the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs marks the first time the Trump administration deals directly with issues of the Congo after the recent flare up where the M23, a Rwanda-backed group, seized the eastern cities of Goma and Bukavu.

Minerals for security

President Tshisekedi appealed to Trump’s deal-making instincts when he reportedly wrote him a letter in February mooting the minerals-for-security deal. Tshisekedi wants U.S. military support to defeat the M23. DRC has had mounting concerns about security with the militia threatening to march on Kinshasa, the capital.

The deal proposed by Tshisekedi is akin to what Trump has in the works with Ukraine where in exchange for investment and security guarantees, the U.S. would access the country’s rare earth minerals in a deal the White House put in the region of $500 billion.

“Nothing is bad. Among those partners we want to exploit our mineral resources are Americans. Here we have Chinese, Japanese, how come we cannot have Americans?” asked Patrick Muyaya, DRC Minister of Communications, in an interview with DW News. DRC officials have said their goal is to diversify their partnerships as a way of leveraging their country’s natural resources.

For years, western mining executives have flocked to Kinshasa to tap into the country’s mineral wealth. Some like Glencore, the Swiss mining giant, which has done business in DRC for decades have faced sanctions in the U.S. and elsewhere for corrupt practices. There is now a renewed push for American companies to snap up the opportunity with a businessman as U.S. President.

Any U.S –DR Congo deal risks harming America’s appearance of neutrality towards Rwanda. This could weaken America’s ability to deliver peace in the complex situation even if it pours in more weapons and enables Tshisekedi’s troops to achieve battleground success against the M23.

Lobito Corridor

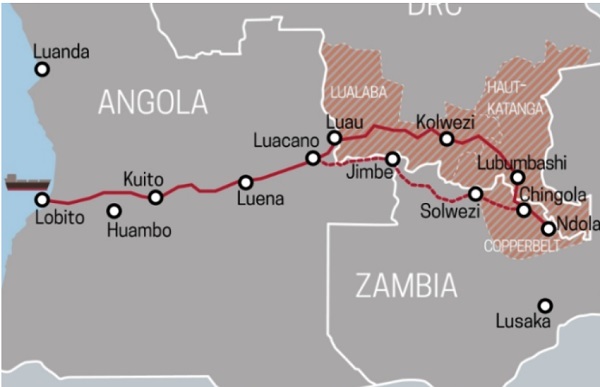

But there is more reason why the U.S. has its eye on DRC: the Lobito Corridor, a 1300 km railway line that stretches from the Angolan port of Lobito, snaking its way in the Congo and into the copper belt of Zambia. The Lobito Corridor was established in the early 1931 but today it is managed by a concession controlled by European companies and supported by the U.S.

Reports say the U.S. has invested about $4 billion in corridor projects. Former US President Biden discussed the project with his Angolan counterpart Joao Lourenco when he visited Angola in December just before leaving office.

Along the corridor lies the Kamoa-Kakula complex which is said to be the world’s third largest mine producing an estimated 600,000 tonnes annually of copper, platinum-group metals, nickel, zinc and other metals essential for the world’s transition to clean energy and a low-carbon economy.

The Lobito Corridor offers the opportunity to transport minerals from the DRC–which has two thirds of the world’s cobalt reserves–-to international markets. However, experts have pointed out that the expansion of these critical minerals supply chains by new venture partners does not resolve the question of equitable resource management where one global player replaces another to perpetuate a cycle of exploitation.

In effect, the corridor merely offers the U.S. an opportunity to counter China’s influence in the DRC. The Tenke Fungurume (TFM) mine, the largest in the world, contains 3.3 million tonnes of the metal. It is controlled by China Molybdenum Company (CMOC), a Chinese company which acquired it from an American firm, Freeport-McMoran.

The Lobito Corridor Investment Authority says the railway infrastructure is Washington’s alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The U.S. is making these moves because China controls 60% of global rare earth mining and 90% of rare earth processing capacity according to DevTech, an international consulting firm.

U.S. interests in DRC’s mineral industry are being looked at in the aspect of strategic competition with China. “Not intervening in CMOC’s acquisition of TFM is arguably the most significant commercial misstep the United States has made in Africa. Consequently, China now owns or holds stakes in 15 of the largest copper and cobalt mines in the DRC,” says Gracelin Baskaran, Director, Critical Mineral Security Program at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in a brief about critical mineral cooperation between the U.S. and DRC.

Baskaran argues that challenges like the ongoing conflict, a tough business environment, Chinese market dominance and poor infrastructure present an opportunity for the U.S. “To succeed, the United States must create a mutually beneficial framework for engagement. This will require legislative changes, deployment of strategic capital, and provision of technical assistance, she adds.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price