According to World Bank data, in 2017, Uganda’s per capita healthcare spending was at $38.4, which is little less than a half of the $78.3 average per capita healthcare spending of non-high income Sub-Saharan African countries

COMMENT | Dr Bruce Tumwine Rwabasonga | It has been 108 days and two million confirmed cases worldwide, since a cluster of strains of pneumonia that were later to be identified as a Novel Coronavirus were reported in Wuhan, China. Since then, a historical pandemic whose scale and impact had not been seen since the 1918 H1N1 Influenza pandemic has swept across the entire world. As epidemics and disease burden generally goes, COVID-19 has not disproportionately impacted Sub-Saharan Africa as typically seen in these cases.

While the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Africa is ever-evolving, one thing that has become abundantly clear is that the continent cannot continue to delegate funding of an essential service like healthcare to its resource rich development partners. In Uganda’s case, in 2016/17, development partners’ contributions formed 42.6% of its current healthcare expenditure (CHE).

On April 14, 2020, President Trump overnight slashed over $400 million that roughly accounted for fifteen percent of WHO’s budget in an unprecedented move. God forbid, had the US instead cut its contribution to Uganda’s healthcare system, then Uganda’s COVID-19 response would have been crushed overnight and millions of Ugandans forced to face a highly virulent and lethal illness on their own. Granted that this scenario is highly unlikely, what is likely is that the developed world faced with contracting economies (as a result of the pandemic) will over the coming year(s) be forced to heavily cut non-mandatory spending – under which funding of other countries’ health systems definitely falls.

The pandemic in this way will be the proverbial last straw on a camel’s back, as heavy donor aid cuts have been ongoing for a while now mainly as a result of the emergent nationalism trend. In the last five years alone, two major aid donors, the US and Britain have voted in to office two leaders whose successful campaigns ran on promotion of nationalism and scaling back on their countries’ global footprint.

The good news is that Uganda in its COVID-19 pandemic response, has demonstrated that it is capable of developing and sustaining a strong healthcare system that can protect and keep its citizens safe at a time of need. This has been evidenced by a robust public health surveillance system that has so far been able to detect, test and treat the most at risk while containing farther spread through contact testing. What has been even more impressive, has been the country’s ability to conduct clinical research.

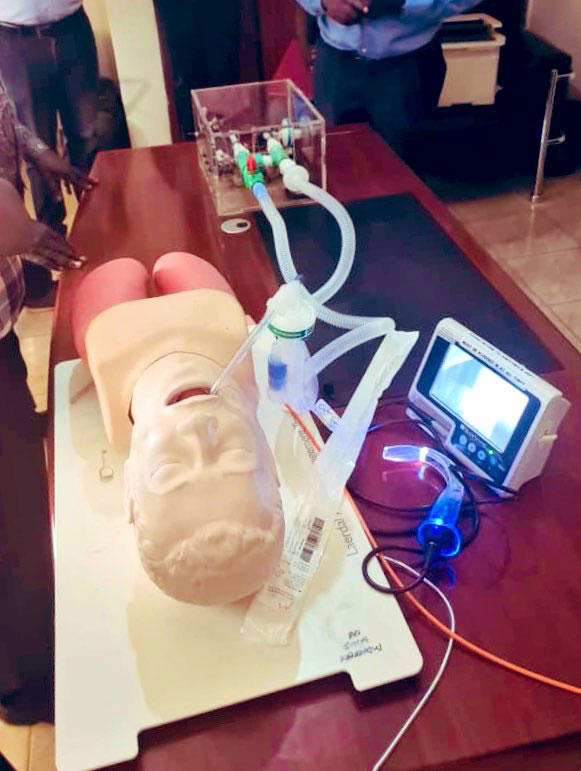

The clinical research conducted at Makerere University has so far provided a glimpse of hope at the country’s ability to locally source much needed technology and supplies like the low cost STDS-Agx (Swab tube dipstick agglutination) COVID-19 test kits and ventilators.

So how can Uganda build on this success and lessons learnt to develop a robust and self-reliant healthcare system?

There are three major components of a functional national health system. That is; a strong public health system, an accessible, affordable and high-quality healthcare delivery system and a funding mechanism to bankroll the first two components.

A strong public health system ensures a robust disease and health conditions surveillance system, develops policies and interventions to mitigate any illnesses that pose a risk to its population and provides oversight and regulation of the healthcare system. An accessible and high-quality healthcare delivery system is characterized by well-run, appropriately staffed and fully equipped service areas e.g. clinics and hospitals that provide preventive, rehabilitative and curative services. The optimal functioning of the first two components is reliant on the third component – securing a sustainable funding mechanism.

In each of these components of a national health system, Uganda has attained a certain level of success while maintaining well-documented shortcomings.

For example, as a result of the services delivery decentralization policies of the 1990s and 2000s, access to healthcare significantly improved through construction of health facilities across the country. However, the impact of these health facilities was mitigated by well documented stories of drug shortages and under-staffing. Likewise, despite having a tax base of a little less under a million people to support over forty million lives, Uganda has managed to innovatively use stakeholder partnerships to keep the healthcare system ‘lights on’.

With that said, continuing to fund its healthcare system with a little less than a half of what the average, non-high income Sub-Saharan African country does, won’t help the country to achieve its desired healthcare system goals.

According to World Bank data, in 2017, Uganda’s per capita healthcare spending was at $38.4, which is little less than a half of the $78.3 average per capita healthcare spending of non-high income Sub-Saharan African countries. Therefore, if there was a magic wand that would address Uganda’s healthcare system issues, it would be sufficient and sustainable funding.

While many strategies have been suggested including mandatory allocation of a significant portion of the national budget to healthcare financing, most of these strategies are neither enforceable nor sustainable in the long run. On the other hand, development and implementation of a national health insurance system as seen in the developed world is both enforceable and sustainable. Of course, this isn’t a new concept and the plan to implement it has already been postponed this year as it has been over the last decade. While it is easy to see why this wouldn’t be a popular initiative given the government’s record on management of public funds and the need to raise additional taxes during an upcoming election, it is just as social distancing, the sour tasting and inconvenient medicine that the country’s healthcare system needs to be cured.

It is naive to believe that the national insurance system will immediately fix Uganda’s healthcare financing issues. It won’t by a long shot! It is however an important first step in working towards development of a sustainable healthcare financing mechanism in Uganda.

The timing for this change couldn’t be better politically as the entire country is currently rallying around its healthcare system! As the bible says in Proverbs 26: 11, “Like a dog that returns to his vomit is a fool who repeats his folly”, let us learn from the threats that exist to the health of all Ugandans and begin today to develop a sustainable and autonomous health system that doesn’t exist at the whims of development partners.

******

Dr. Rwabasonga is a physician, public health professional and healthcare services consultant based in Washington DC.

Dr. Rwabasonga is a physician, public health professional and healthcare services consultant based in Washington DC.

Email: Mande166@umn.edu

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price