Africa bank lists economy among best in Africa

COVER STORY | THE INDEPENDENT | Just days to the June 14 reading of the national budget in parliament, the African Development Bank (AfDB) has listed Uganda among countries whose good GDP growth performance is expected to make Africa the second fastest growing region in the world after Asia.

“African economies are moving in the right direction,” said AfDB Group President Akinwunmi Adesina, noting that five of the six pre-pandemic top-performing economies are set to be back in the league of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies in 2023–2024.

The 220-page report launched on May 23 said African economies remain resilient amidst multiple shocks with average growth projected to stabilize at 4.1 percent in 2023–24, higher than the estimated 3.8 percent in 2022. Africa’s growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) was estimated at 3.8 percent in 2022, down from 4.8 percent in 2021 but above the global average of 3.4 percent. The growth slowdown was attributed mainly to the tightening global financial conditions, and supply chain disruptions exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, subduing global growth. Growth was also impaired by the residual effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the growing impact of climate change and extreme weather events.

The report said while the deceleration was broad-based, with 31 of the 54 African countries posting weaker growth rates in 2022 relative to 2021, the continent performed better than most world regions in 2022, with the continent’s resilience projected to put five of the six pre-pandemic top performing economies; Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Tanzania back in the league of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies in 2023 –24.

The report said growth is projected to rebound to 4 percent in 2023 and consolidate at 4.3 percent in 2024, underpinning Africa’s continued resilience to shocks. The forecast for 2023 has been maintained as predicted in the January 2023 edition of Africa’s Macroeconomic Performance and Outlook (MEO) published by the African Development Bank Group. However, due to expected slight improvements in medium-term global and regional economic conditions- mainly underpinned by China’s re-opening and slower pace of interest rate adjustments the forecast for 2024 has been revised up by 0.4 percentage points relative to the January 2023 MEO projection. Despite this, climate change, elevated global inflation, and persistent fragilities in supply chains will remain on the watch list as potential factors for possible slowdowns of growth in the continent, the report said.

Uganda outlook

GDP growth in Uganda is projected to exceed 5 percent in 2023 and 2024 on account of developments in the oil sector.

Uganda’s Real GDP grew an estimated 6.3% in 2022, more than the 5.6% in 2021, according to the report. This despite higher commodity prices, tighter financial conditions fueled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and continued global supply chain disruptions.

Agriculture, notably food crops, performed well, supported by good rains, while growth in industry weakened as output in construction waned. Services also performed well as trade and repairs and the health subsector demonstrated strong growth.

During 2022, the Uganda shilling depreciated 3.8% against the U.S. dollar. Inflation was 7.2%, driven by a 14.9% increase in food prices and a 12.7% increase in energy prices.

Higher food and energy prices pressed households, especially subsistence farmers and urban dwellers.

To curb inflation, the Bank of Uganda raised the policy rate four times in 2022, from 6.5% to 10%. The financial sector remains well capitalized, with a capital adequacy ratio of 21.7% in 2022.

Higher public investment in roads, interest costs, and other non-wage spending stoked fiscal deficits until 2020. Since then, the government has slowed the pace of investment, reducing the deficit to 7.4% of GDP in 2021 and an estimated 5.3% in 2022. The deficit was financed through public borrowing, rising to 50.3% of GDP in June 2022. Risk of public debt distress is moderate, and public debt remains sustainable. The current account deficit remains elevated, at 8.6% of GDP, attributed to rising imports and lower tourism receipts after the COVID-19 pandemic, which were exacerbated by a short Ebola outbreak in 2022.

Outlook on risks

Uganda’s GDP is projected to grow 6.5% in 2023 and 6.7% in 2024, assuming any global growth slowdown will be short lived. This expansion is projected to be supported by stronger growth in East Africa, while the Chinese economy has eased lockdowns, reducing global supply chain disruptions, supporting higher growth.

Following the final oil agreements in 2022, the oil sector is ramping up investments, underpinning growth beyond the medium term. Although inflation is expected to slow, it is projected to remain above the central bank’s medium-term target of 5%. The fiscal position is projected to improve, reflecting consolidation efforts. External risks are tilted toward the downside, notably a prolonging of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and continued supply chain disruptions, while pockets of regional insecurity continue to pressure security-related spending. Domestic risks relate to unexpected increases in public spending on infrastructure amid weak tax revenue.

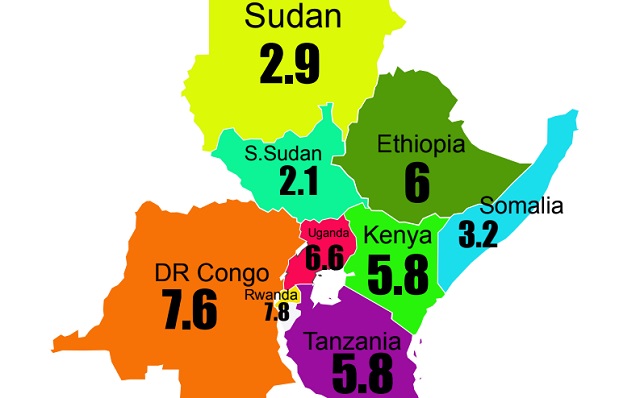

East Africa outlook

Growth in the East African region is expected to consolidate at above 5 percent in the medium term. High growth will be anchored on Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Uganda (which together account for 41 percent of the region’s GDP), the report says. Rwanda has consistently grown by 7 percent or more, except in 2020, and is projected to sustain this momentum in 2023 and 2024.

For Ethiopia, GDP growth is expected from continued infrastructure spending. Growth in Rwanda will be driven by higher public infrastructure spending and mineral exports, boosted by value addition in minerals through enhanced investment.

Djibouti, Kenya, and Tanzania are also expected to sustain their recent gains. Sudan’s projected higher growth of 2 percent in 2023 and 3.8 percent in 2024 is subject to downside risks, including the political impasse. South Sudan may not return to positive growth until 2024.

East Africa has experienced better economic performance and was the only region that escaped a recession during the COVID-19 pandemic, underpinned by its more diversified production structure. Its growth momentum moderated to 4.4 percent in 2022 from 4.7 percent in 2021 but is projected to rise strongly to 5.1 percent in 2023, firming up to 5.8 percent in 2024. Since most countries in the region are net importers of commodities and bear the brunt of high international prices, especially for energy and food, high commodity prices often translate into slower growth, as in 2022, and this remains a concern for the medium-term outlook. The region is also prone to recurrent climate shocks such as drought, particularly in the Horn of Africa, and pockets of fragility, including internal conflicts. The slowdown in 2022 was attributed mainly to these shocks, exacerbated by disruptions in global supply chains. Tight monetary and fiscal policy to rein in inflation has also constrained domestic consumption, compounded by contractions in agriculture and manufacturing activities, weak growth in credit to the private sector, and the rise in public debt.

Higher energy and food prices have severely strained government budgets in countries such as Malawi, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Togo with fiscal deficits exceeding 7 percent of GDP. In contrast, other countries including Djibouti, Mauritania, and Somalia managed to maintain fiscal deficits at less than 1.3 percent of GDP despite the challenging economic and financial environment. These countries helped to contain the average deficit for the group at 5.5 percent of GDP in 2022. The average fiscal deficit for non-resource-intensive countries is projected to decline to 4.7 percent of GDP in 2023 and 4 percent in 2024, as the expected decline in food and energy prices will put less pressure on the group’s revenues.

Mobilizing finance

The theme of the 2023 African Economic Outlook is Mobilizing Private Sector Financing for Climate and Green Growth in Africa.

In line with this theme, the report notes that although the global landscape for private sustainable green finance is expanding, Africa is still struggling to fully leverage this expansion and increase its share. Private sustainable financial flows to developing economies reached US$250 billion in 2021, with 59 percent of it in green bonds.

Green loans, sustainability bonds, sustainability-linked loans, sustainability- linked bonds, and social bonds accounted for the rest. Although most of this went to Asia and Latin America, the emergence and growth of this market show the potential of scaling these and other innovative instruments to drive climate action and green growth in Africa.

For green bond issuance in 2022, Africa accounted for just 0.1 percent of the global total, far below its economic size (2.8 percent of global GDP and 17 percent of the world population).

Just three countries Benin, Egypt, and South Africa dominated the market, accounting for more than 90 percent of total green bonds in 2022, with South Africa alone accounting for more than 66 percent and Egypt and Benin for 25 percent together.

In addition to Nigeria and Morocco, which have also issued green bonds, Kenya, Namibia, and Tanzania have recently entered the market, broadening opportunities for improved liquidity and pricing.

Debt-for-nature and climate swaps have existed in different forms for decades but in recent years have gained in popularity, especially as the cost of sovereign borrowing has become prohibitive for African countries. These instruments can reduce the fiscal burden of external debt and have been used in countries such as Cameroon, Ghana, and Madagascar.

The report says, although green taxonomies have been under consideration for some time across the continent, only South Africa has so far developed a taxonomy for green investments. Countries should develop national green taxonomies, green and sustainable finance standards and frameworks that complement those developed by international organizations to align with international best practice. In doing so, countries can ensure that the governance of private finance is streamlined, while also demonstrating transparency and accountability in mobilizing and using private investments and attributing impacts.

Although many African countries have still not implemented comprehensive fiscal incentives for private finance, some show that there is still an opportunity for others to do so. Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Morocco, Rwanda, and Tunisia have devised policies and mechanisms to offer fiscal incentives to attract external private investments.

For example, the report says, Kenya, Morocco, Rwanda, and Tunisia have duty and value added tax (VAT) exemptions for renewable energy and energy efficiency-related investments. Ghana, Mauritius, South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia have used auctions to enhance renewable energy generation. Kenya and Morocco have removed pre-existing incentives for activities that dis-incentivize green growth, such as subsidies on petroleum products.

But the report warns, in some cases, fiscal incentives could have greater costs than benefits. For example, they may be made available to investors that would have invested anyway or whose investment decisions are influenced by other factors, such as geographical location, and not whether (or not) they receive these incentives.

“African countries thus need to think carefully about how these incentives should be designed and offered,” the report says, “Tax incentives to firms are one and often not the determining factor for private investment decisions. Some investors (such as those that are efficiency-seeking) may be more sensitive to incentives than others (such as market-seeking or natural resource-seeking).”

But that the effect of these incentives on investments in low-income countries is smaller than that in high-income countries, and most firms would invest even without incentives.

Climate finance

The report says Uganda’s estimated climate finance needs are US$17–$28 billion during 2020–30, with an average financing gap of US$1.3–$2.2 billion a year.

“The government will need to mobilise private investment to close this gap,” the report says, “The private sector is financing projects in agriculture, forestry, and renewable energy, but more is required.”

The report says to achieve the Nationally Determined Contribution targets, investment of US$880 million–US$2.3 billion is needed in renewable energy. It says Uganda can tap into its natural capital to finance climate change and green growth while emphasizing sustainability.

The country already faces overexploitation of renewable natural capital, especially forest land, which has shrunk to 9% from 25% in 1990. Sustainable exploitation and replenishment of forests must take center stage.

Uganda has large deposits of nonrenewable natural capital: oil and gas, iron ores, and “green” metals that can be sustainably exploited. The country is expected to produce 230,000 barrels of crude oil a day from 2025, generating substantial revenue. These resources could be channeled into green technologies.

Green metals and iron-ore deposits could be developed using technologies for greening manufacturing and construction to provide the basis for transforming to a green economy. To attract the right investors, stronger accountability and transparency will be required, the report notes.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price