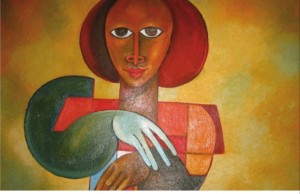

Artworks shaped by a life of observation

Kizito Maria Kasule is an art scholar and practicing painter who has been heavily influenced by circumstances, the environment and imagination almost in equal measure. Through his over a quarter century practice, he has gone through many seasons and transitions and now occupies a space that one could describe as being fully ‘decolonised’ from peripheral influences. He enjoys an independence of mind in his visual praxis, which is occasioned his critical interactions with a diversity of cultures through observation and study.

Kizito Maria Kasule is an art scholar and practicing painter who has been heavily influenced by circumstances, the environment and imagination almost in equal measure. Through his over a quarter century practice, he has gone through many seasons and transitions and now occupies a space that one could describe as being fully ‘decolonised’ from peripheral influences. He enjoys an independence of mind in his visual praxis, which is occasioned his critical interactions with a diversity of cultures through observation and study.

Kizito has achieved in academia what most artists would forever dream of; a bachelors degree, two masters degrees and a PhD. While he had hoped in 1992 after his first degree to throw around the weight of his academic credentials as a means to break into the competitive art scene, he was to rudely learn that art dealers of the time were more interested in the art produced by informally-trained (read self-taught) artists.

Their argument then was that academically equipped artists had ‘sacrificed their African souls’ at the altar of Western precepts and thus not worthy of their attention. Kizito was turned away by a number of art galleries he approached to exhibit his work, including the prominent Watatu Gallery in Nairobi that is famous for promoting self taught artists such as the Ugandan legend Jak Katarikawe.

Whereas this experience caused some measure of disenchantment in him, he decided to abandon the idea of public shows and pursue his formal art nonetheless. It was during his study in Ireland that he picked interest in working from primary sources and observation.

For example, he came to the realization that working from observation is not

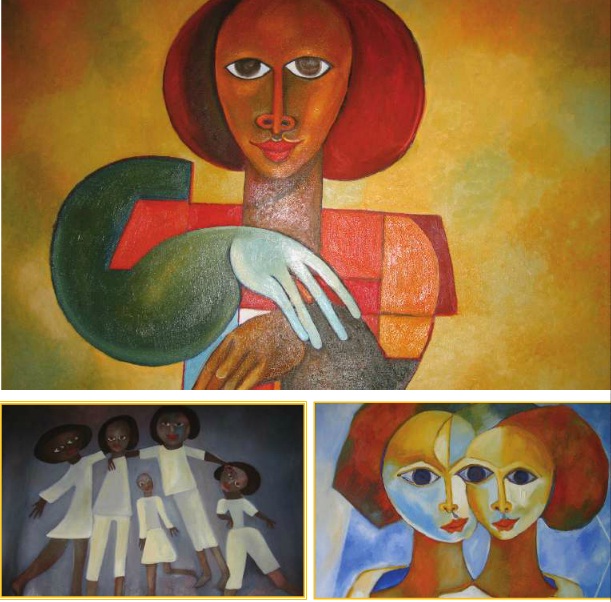

simply about replicating nature but rather entails the emotional interpretation of the same. This contributed to the furtherance of his deep-seated defiance that we are to witness not only in his future works but also his oral arguments. For instance, one time in 2015 he had left his work in progress at his home studio when his daughter picked up a brush and generously spread paint over the works.

She also used chalk and other media to draw cartoons thereon. Discovery of the mischief initially threw Kizito into fits of rage. However, a critical scrutiny of the ‘damage’ ticked off a sudden revelation that flung him into another dimension of art that he had never imagined.

This led him to invite all his children to pick up brushes and create templates for his subsequent works, where he would rework the infant forms into mature works of art that he would otherwise never envisage before the ostensible misfortune.

It is very significant to recall that the education experience that Kizito Maria underwent did not only affect his personal vision of art but also influenced the wider fraternity in which he operated in Uganda. He observed that the Makerere art school was languishing in the quagmire of history and yet the very precursors of formalism (British colonialists) that introduced it at the art school had since moved many strides ahead in search of new possibilities.

With the support of his colleagues, Kizito instigated a quiet campaign of helping the school engage another gear that would move it to another level without delay. His approach was regarded by the majority as too radical and, predictably, there was real resistance from the nostalgic staff that sought to maintain the status quo. Today Kizito is the Dean of the Makerere art school and it would be interesting to know how this position of authority is working in his favour to toe his path of defiance unfettered.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price