New report says government underestimates the true magnitude of maternal, child death in hospitals

Sarah Nakaggwa had a clue on what happens when a woman is about to give birth. She was expecting her fifth child. So when she started to notice changes, she and her husband, Moses Mutongole, checked into St. Francis Hospital Nsambya, one of the top hospitals in Kampala. She had been getting antenatal care here.

A day later on Aug.19, even with the labour pains increasing the baby kicks suddenly went silent. The desperate couple was dispatched to Kawempe General Referral Hospital for further attention. But about 15 minutes into the journey she had a still birth inside the ambulance. Despite appearing to be recovering from the shock of losing a baby, on Aug.24 she was added to the ugly statistic of women who have died due to child birth related complications. Up to 16 women die per day due to birth related conditions – according to official figures.

Mutongole says after the still birth, they got admitted to Kawempe Hospital on Aug. 22. Kawempe is a new extension of Uganda’s main hospital, the Mulago National Referral and Training Hospital, also in Kampala, which is under renovation. Mutongole says despite its high position in the hierarchy of hospitals, he counted seven women who died that day in its High Dependence Unit. Four babies died. The next day he says about 10 babies died.

Mutongole is to date not sure what exactly caused his wife’s death. He paid for postmortem services, but was never given a report showing what killed either his wife or his child.

If proved Mutongole’s case is a blotch on the Ministry of Health which boasts of recording and reviewing the cause of death of every mother or child death every day. As recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), hospitals are supposed to conduct perinatal and maternal death reviews. The objective is to identify the cause and forge ways of preventing the deaths from happening.

When The Independent spoke to Dr. Livingstone Makanga the coordinator of these reviews at the Ministry, he said they are notified of such deaths within 24 hours either through Mtrac; an ICT platform used on a mobile phone where they get SMS alerts from the people or through their team members at the health facility.

Within seven days, an audit of the deaths is done to review the circumstances including whether a mother attended antenatal, whether it was delay to access health facility, or negligence on the side of health workers.

Makanga says they record every death of a baby 28 weeks before delivery to 28 days after delivery which is technically categorised as a perinatal death and death of a pregnant woman up to 42 days after delivery – considered a maternal death.

According to him, districts present a report to the Ministry by the 7th day of every new month and that recently have added a new aspect where even deaths that occur outside a health facility are recorded through the Village Health Teams (VHTs).

Makanga said his National Maternal Perinatal Death Review (MPDR) committee has been religiously recording these deaths over the last five years and that maternal mortality rate stands at 438 per 100,000 live births whereas perinatal death stands at 27 per 1000 births. But he could not give details of the total deaths registered every year and their variations. Makanga possibly has a valid reason for not releasing these figures.

However, it is such omissions that WHO, in a new report, is basing on to warn that maternal deaths figures released by agencies such as Makanga’s might not present the true picture. According to WHO, such official reports sometimes underestimate the true magnitude of maternal mortality by up to 30% worldwide and 70% in some countries.

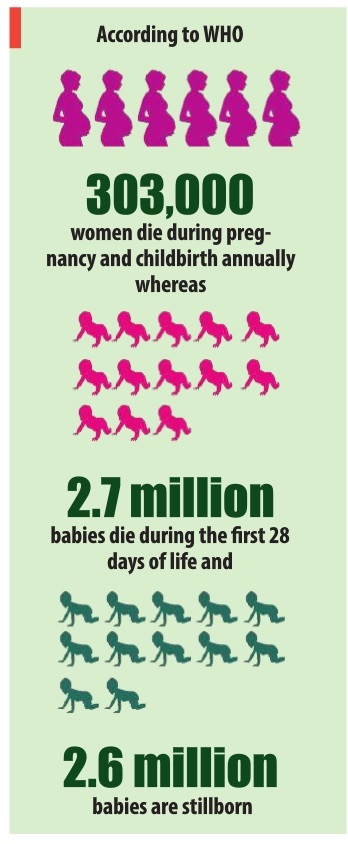

According to WHO 303,000 women die during pregnancy and childbirth annually whereas 2.7 million babies die during the first 28 days of life and 2.6 million babies are stillborn. Nearly all babies who are stillborn and half of all newborn deaths are not recorded in a birth or death certificate, and thus have never been registered, reported, or investigated by the health system.

When it comes to Uganda, the figures that Makanga quotes were first released in 2011 when the National Demographic and Health survey was conducted.

“The Uganda Demographic survey which is ongoing will give us more accurate data. I may not know which regions record more deaths but I know facilities like Mulago record more cases because it’s where all critical cases are referred,” Makanga says.

Dr. Nathan Kenya Mugisha, a former Director of Health Services at Ministry of Health told The Independent that by coming up with the reviews, policy makers were hopeful that reviewing these deaths would lead to a complete record of the deaths and good attribution of causes of death. In turn, these records could lead to formulation of measures to stop such tragedies from happening again since most of them are avoidable with improved quality of care.

“I don’t know whether the reviews are being done as was recommended,” he said, “But what I know is deaths have decreased.”

Mugisha actively took part in formulating the National Maternal and Perinatal Review Strategy.

New guidelines

To tackle the problems faced by review committees like Makanga’s MPDR in monitoring and recording the deaths, WHO on Aug.16 launched another three new publications. Their aim is to guide the committees and improve the data. One of them is a standardised system of classifying deaths where they link a death to what caused it, a tool that will be used across all low, middle and high income countries in a consistent way.

The second publication dubbed `Making Every Baby Count: Audit and Review of Stillbirths and Neonatal Deaths’ will guide countries to review and investigate individual deaths so they can recommend and implement solutions to prevent similar ones in the future.

The third publication: `Time to respond: a report on the global implementation of maternal death surveillance and response’, is to help countries strengthen their maternal mortality review process in hospitals and clinics.

Unlike the previous guidelines, the new documents have specific information on establishing a safe environment for health workers to improve quality of care within clinics and an approach to recording deaths occurring outside the health system, such as when mothers deliver at home which too was previously missing.

Whether the new guidelines will be followed, especially in Uganda where they still have challenges with the old system is still the question.

Makanga is hopeful that they will do better now that the Ministry of Health is working with the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and National Identification and Registration Authority (NIRA) to get more accurate data. He says this will help them take effective decisions to prevent more mothers and babies from dying.

For Dr Mugisha, merely targeting of resources into child and maternal health programmes may not yield as much results. He says issues of maternal and child health go hand in hand with growth and development of the country. To him as long as the country is growing, maternal and prenatal mortality will be decrease because it has a lot to do with how educated people are, whether they have money to afford proper nutrition or go to the hospital early enough.

****

editor@independent.co.ug

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price