New survey shows shift away from democratic culture

COVER STORY | THE INDEPENDENT | Ugandans are growing increasingly more uninterested in elections and elected leaders and, they see little hope in the opposition providing better leadership than the current one of President Yoweri Museveni.

That is the general view based on findings by the latest survey report by Afrobarometer which is a pan-African, independent, non-partisan research network that measures public attitudes on economic, political, and social matters in Africa.

In its latest report released on July 02 in Kampala, Afrobarometer said there has been an observed increase since 2008 in the opinion that, in Uganda, political competition often or always leads to violent conflict. The report noted that this is “undermining democracy and decreasing the appeal of political parties.”

Afrobarometer Uganda’s lead consultants also said in the launch presentation that electoral and political violence, particularly during elections, is linked to declining political party identification, support, trust, and perceptions of election quality.

“Both ruling and opposition political parties must realign their programmes to better reflect the public’s aspirations for democracy and democratic norms,” they said.

According to the Afrobarometer report, Ugandans appear to see the government as either a hybrid or authoritarian regime. In comparison, Tanzanians, Zambians, Mauritians, Namibians, and Sierra Leoneans have a higher perception of full democracy in their countries.

It is, therefore, not surprising that support for democracy in Uganda has been declining together with rejection of authoritarian alternatives, according to the report.

Respondents’ views

Respondents were asked: Which of these three statements is closest to your own opinion? Statement 1: Democracy is preferable to any other kind of government. Statement 2: In some circumstances, a non-democratic government can be preferable. Statement 3: For someone like me, it doesn’t matter what kind government we have. There are many ways to govern a country.

They were further asked: Would you disapprove or approve of the following alternatives: Only one political party is allowed to stand for election and hold office? The army comes in to govern the country? Elections and Parliament are abolished so that the president can decide everything?

The percentage fully committed to democracy are those that prefer democracy and reject military rule, one-man rule, and one-party rule. In 2012, up to 92% rejected one-man rule. In 2024 that figure has dropped by one percentage point to 91%. In 2012, up to 82% rejected one-party rule. In 2024 that figure dropped to 81%.

In 2012 up to 89% rejected military rule. In 2024 that figure has dropped to 84%. In 2012 up to 79% preferred democracy to any kind of rule. In 2024 that figure has dropped to 77%. In 2012 up to 63% Ugandans were committed to democracy. In 2024 that figure has dropped to 54%.

Another major concern is for political leaders’ need to find a lasting solution to foster a harmonious environment for multiparty politics in Uganda. Respondents were asked: Which of the following statements is closest to your view?

Statement 1: We should choose our leaders in this country through regular, open, and honest elections.

Statement 2: Since elections sometimes produce bad results, we should adopt other methods for choosing this country’s leaders. (% who “agree” or “agree strongly” with Statement 1)

On the whole, how would you rate the freeness and fairness of the last national election, held in 2021? (% who say “completely free and fair” or “free and fair with minor problems”).

In answer to statement 1, up to 83% of respondents supported elections. However, that was the second lowest figure in the six years that Afrobarometer has asked Ugandans that question. In the 2012 survey, 88% supported elections. In 2019, it was 78%. This shows that Ugandans support for elections is high but fluctuating with a declining trend. In an interesting twist, Ugandans were often compared with those of neighbours Kenya and Tanzania and in a few occasions with at least 39 countries out of 54 in Africa.

On whether the 2021 general election were free and fair, for example, only 55% Ugandans said they were free and fair. That graph also showed fluctuation with a declining trend. It was 69% in 2015 regarding the 2011 elections.

Continent-wide, however, Uganda’s scores on support for elections for choosing leaders appear relatively decent and place it among the top 10 best performers on free and fair elections. However, on the question of whether the elections are free and fair, Uganda fairs badly and only countries like Zimbabwe, Sudan, Congo-Brazzaville, Mali, Gabon and Morocco are worse.

On voter intention and trust by the ruling and opposition political parties in 2024, the ruling NRM trounces the opposition parties. The respondents were asked: If presidential elections were held tomorrow, which candidate’s party would you vote for?

They were also asked: How much do you trust the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say: The ruling party? Opposition political parties (% who say “somewhat” or “a lot”).

In response to the question on the party they would vote, up to 55% said they would vote ruling party, NRM. That was a decline from the 71% who said they would vote NRM in 2015, just before the 2016 elections.

On the question of trust, the opposition suffered equally bad perception with only 33% trusting it.However, it is far higher than the 19% who said they would vote opposition in the 2024 survey.

Up to 56% trust the ruling party.

Significantly, however, the trust curve for the opposition is relatively flat; meaning it’s neither gaining voter trust nor losing it. However the trust cover for the ruling party is falling sharply, meaning that it is losing the trust of voters. In 2015 for example that trust was 71% but dropped to 52% in 2022.

A similar pattern can be seen on the question of political party identity and trust. Respondents were asked: Do you feel close to any particular political party? They were also asked: How much do you trust the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say: The ruling party? Opposition political parties?

Again the opposition was badly rated, with only 33% saying they feel close to a ruling party. But that is close to their score in previous surveys and so, the opposition political party curve is relatively flat.

The opposition has performed equally dismally in previous surveys. For example, respondents were asked: Qn: With respect to the upcoming 2021 general elections, how much do you trust each of the following institutions to do their best to ensure that the elections are free, fair, credible, and peaceful: The Presidency? The Electoral Commission of Uganda? Uganda Police Force? Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces? The NRM party? Opposition political parties? Courts of law? Local and international election observers? The opposition scored the lowest level of trust at 44%. The ruling NRM was at 45%, and Electoral Commission at 48%, Police 47%, and UPDF 49%. Local and international election observers scored highest at 59%.

The ruling party curve, meanwhile, shows fluctuations with a declining trend from 71% trust in 2015 to 61% trust today.

In another question: Respondents were asked: Do you feel close to any particular political party? [If “yes”:] Which party is that? Only 14% said they feel close to an opposition party. That was a steep decline from the 18% who said they feel close to an opposition party in 2022. In comparison, up to 42% said they feel close to the ruling NRM party. That is far higher than the score for the opposition but it looks like bad news for the ruling party because, once again it is a sign of lukewarm connection between the people and the ruling party. Its support is neither growing nor declining.

On the other hand, the number of people who do not identify with either the ruling party or the opposition is growing steeply. These are people who are likely not to vote in 2026 unless they are courted, persuaded, and mobilised by either the ruling party or the opposition. In 2012 they were just 31%. But their number has been going up and they now number more than those who feel close to the ruling NRM at 44%.

Another interesting, if not confusing response was on views on political opposition as a viable alternative. The respondents were asked: Please tell me whether you agree or disagree with the following statement: The political opposition in Uganda presents a viable alternative vision and plan for the country. (% who “agree” or “strongly agree”).

Up to 62% said either they agree or strongly agree. That was a huge jump from the 46% who said so in 2021. Based on the other lukewarm responses, this response appears odd. How could voters not feel close to the opposition when they perceive it as a viable alternative to the ruling party?

Ugandans yearn for democracy

Equally mixed are the perceptions of Ugandans on multi-party democracy. According to the survey report, Ugandans rank third in Africa on belief that more political parties are needed in the country. According to the report up to 79% of Ugandans want more political parties. Only voters in Congo-Brazzaville and Botswana want more political parties than Ugandans.

Oddly, however, Uganda are equally adamant that political parties breed conflict. Respondents were asked: Which of the following statements is closest to your view? Statement 1: Political parties create division and confusion; it is therefore unnecessary to have many political parties.

Statement 2: Many political parties are needed to make sure that citizens have real choices in who governs them. (% who “agree” or “strongly agree” with Statement 2) In your opinion, how often, in this country, does competition between political parties lead to violent conflict? (% who say “often” or “always”).

In response to statement 1, up to 74% of respondents agreed that political parties create division and confusion; it is therefore unnecessary to have many political parties. In comparison only 27% in Botswana, which equally wants more parties, agreed. The figure for Congo-Brazzaville was 53%. In fact, Uganda was once again among the top 10 countries with the perception that political parties breed conflict.

The others are Tunisia (87%), Guinea (85%), Sudan (80%), and Senegal (82%), and Ivory Coast (80%). But this group of countries equally says they do not need many political parties. Ugandans are an outlier in the sense of saying political parties breed conflict but at the same time saying they want more political parties.

Commitment to democracy

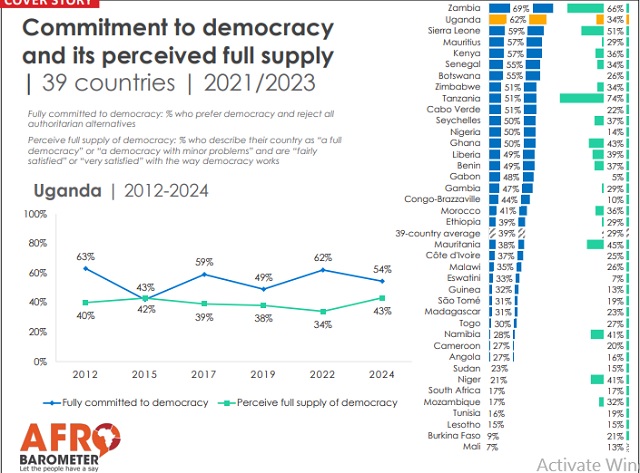

The survey report also has a section on “Demand and satisfaction: Views on democracy and democratic norms.” Under this section, the survey finds that Uganda ranks among the top African countries in its commitment to democracy. But like many of its peers, the country records significantly lower levels of public satisfaction with its democratic processes.

“Ugandans show an interesting demand and supply trajectory, with supply constantly dropping while demand shows a cyclic trend, rising and falling, particularly between general election cycles,” the report say.

The report says since the early 2000, Uganda’s progression toward full democracy has seen significant gains in the demand for democracy rather than in its supply, marking a shift from a predominantly supply-led to a demand-led democratic regime. This observation is made under the sub-header, “Consolidating democracy.”

Democratic consolidation is a political term describing a process by which a new democracy matures, in a way that it becomes unlikely to revert to authoritarianism without an external shock, and is regarded as the only available system of government within a country. It means that no one in the country is trying to act outside of the set institutions.

This is the case when no significant political group seriously attempts to overthrow the democratic regime, the democratic system is regarded as the most appropriate way to govern by the vast majority of the public, and all political actors are accustomed to the fact that conflicts are resolved through established political and constitutional rules.

But when democracy is not consolidated yet, the democratic institutions and processes are not stable enough. Such institutions and processes are curbed by entrenched state-society relations, such as populism, clientelism, and corruption.

For a country to be perceived as democratically consolidated, there must be a durability or permanence of its democracy over time. This includes adherence to democratic principles such as rule of law, independent judiciary, competitive and fair elections, and a developed civil society. Other indicators include two consecutive democratic turnovers of power, the presence of political parties with developed structures and frameworks to promote political publicity, and strong economic development.

Based on this criteria, Uganda’s democracy is not consolidated. The report analyses this situation in two ways. First it looks at the citizens’ full commitment to democracy. This refers to the percentage of Ugandans who prefer democracy and reject all authoritarian alternatives of governance. Second, the report looks at perceptions of full supply of democracy: This refers to percentage of Ugandans who describe their country as “a full democracy” or “a democracy with minor problems” and are “fairly satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the way democracy works in Uganda.

According to the report, Ugandans rank highly in their preference for democracy and rejection of all authoritarian alternatives of governance. But the percentage fluctuates and is declining. In 2022, for example, the figure of Ugandans committed to democracy was 62% and this placed them at number two out of 39 countries surveyed. But this figure dropped to 54% in 2024. Only Zambians said they want democracy more than Ugandans.

However, on the question of how many Ugandans who describe their country as “a full democracy” or “a democracy with minor problems” and are “fairly satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the way democracy works in Uganda, the country scores very badly. This is called full supply of democracy. Only 34% of Ugandans think there is full supply of democracy in their country.

The Economist Group which is best known as publisher of The Economist newspaper and publishes “The Economist Democracy Index” describes full democracies as nations where civil liberties and fundamental political freedoms are not only respected but also reinforced by a political culture conducive to the thriving of democratic principles. These nations have a valid system of governmental checks and balances, an independent judiciary whose decisions are enforced, governments that function adequately, and diverse and independent media. These nations have only limited problems in democratic functioning.

The Economist also defines ‘flawed democracies’ which are nations where elections are fair and free and basic civil liberties are honoured but may have issues. It also has `Hybrid regimes’ with regular electoral frauds, and ‘Authoritarian regimes’ where political pluralism is nonexistent or severely limited.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price