Why growing societal discontent can lead to violence and protests

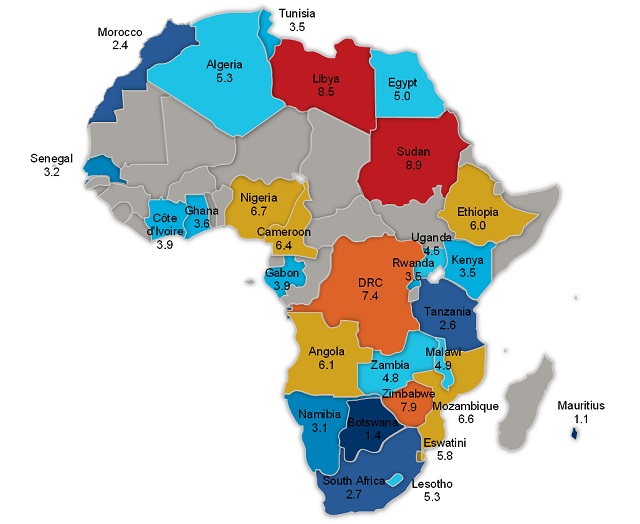

Kampala, Uganda | INDEPENDENT TEAM & AGENCIES | Uganda, political-economically speaking, is moderately stable compared to other countries that are highly unstable such as Sudan and Libya.

On the policy front, this can be seen in the government’s tendency to run high budget deficits as funds are allocated to appease the military or to finance domestic conflict. This in turn leads to rising debt levels, declining access to external funding, and fiscal policies prioritising short-term spending over long-term development.

The country is rendered less stable as growing societal discontent can lead to violence and protests. Furthermore, restricted access to international finance and concurrent budget deficits weaken the government’s ability to provide relief during crises, which amplify the fallout from events like floods, droughts, disease epidemics, and disasters.

These are the views of the UK Firm, Oxford Economics, which boasts of being the world’s foremost independent economic advisory firm with distinguished expertise in forecasting and modelling.

The views are a result of a new political-economic framework which Oxford Economics researchers have developed that models the societal, economic and governance aspects of policy on the African continent and captures the associated risks.

The report by the researchers is entitled: `Africa: Political-economic risks – understanding policy in Africa’ and was published on Dec.14.

In being moderately stable, Uganda is in the same category of risk as Kenya, Rwanda, Zambia, Malawi, Namibia, Egypt, Algeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Gabon and Lesotho. The degree of instability risk varies among these countries; being highest in Algeria and Egypt and lowest in Rwanda and Namibia.

Some countries have less risk of political-economic instability. These include Tanzania, Botswana, Morocco, and South Africa.

According to the Oxford Economics researchers, understanding the interactions between economics and politics is vital to navigate Uganda’s policy environment and the rest of Africa. It requires understanding the relative predictability of policy, the power dynamics, and pivotal actors present in policy formulation.

It also involves looking at the connections between the government, society, macroeconomic climate, and the operational environment, and how these interact with policy over time and whether the interaction is negative or positive.

In other words, navigating the policy environment requires understanding who holds the power. What are the power dynamics embedded in the policy formulation process and what is the relative influence that certain groups have over this process?

Three main actors

In Uganda, and the rest of Africa, there three main actors vying for dominance in the policy-setting arena: the government, the military, and civil society.

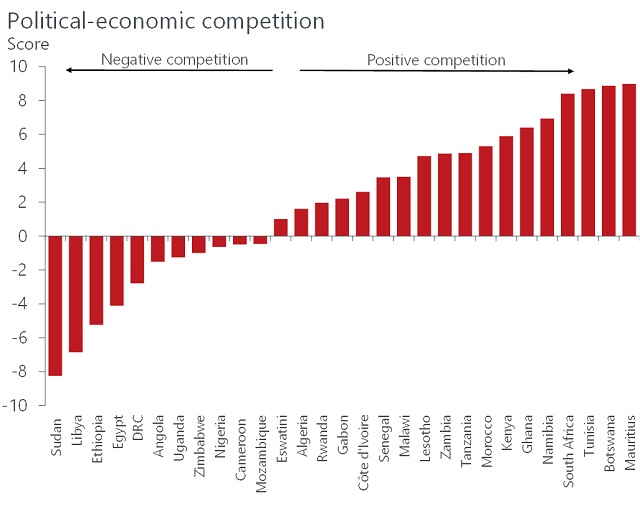

As the makers of policy, the government plays a central role, however, the government’s policy-determining power is not absolute, and it is held in check to varying degrees by either the military (negative competition) or civil society (positive competition).

In Uganda, negative competition and instability interact. This means the country is moderately stable compared to others that are highly unstable such as Sudan and Libya. On the policy front, the government tends to run high budget deficits as funds are allocated to appease the military or to finance domestic conflict. This leads to rising debt levels, declining access to external funding, and fiscal policies prioritising short-term spending over long-term development.

The country is rendered less stable as growing societal discontent can lead to violence and protests. Furthermore, restricted access to international finance and concurrent budget deficits weaken the government’s ability to provide relief during crises, which amplify the fallout from events like floods, droughts, disease epidemics, and disasters.

Their framework consists of two axes: political-economic stability and political-economic competition. Political-economic stability represents the relative predictability of policy while the competition axis speaks to the power dynamics and pivotal actors present in policy formulation.

The researchers say there are two types of political-economic competition: negative and positive. In negative competition countries, the government’s supremacy is challenged by the military or an insurrectionist group. In these countries, policies are inclined to be more short-term focused, budgets prioritise spending on the military and recurring expenses, and security concerns take precedence over individual freedoms. Countries like Sudan, Libya, and Ethiopia are ranked high on this list, and they tend to be less stable compared to their positive competition counterparts.

In positive competition countries, civil society groups serve as the main checks on the government’s power. In these countries, policies tend to be more inclusive and transparent, budgets are relatively predictable and promote economic growth, and developmental policies generally take priority. Countries like Mauritius, Botswana, and South Africa fall into this category. While these countries can still experience destabilising events, they tend to recover quicker than their counterparts and are generally more resilient in mitigating the fallout.

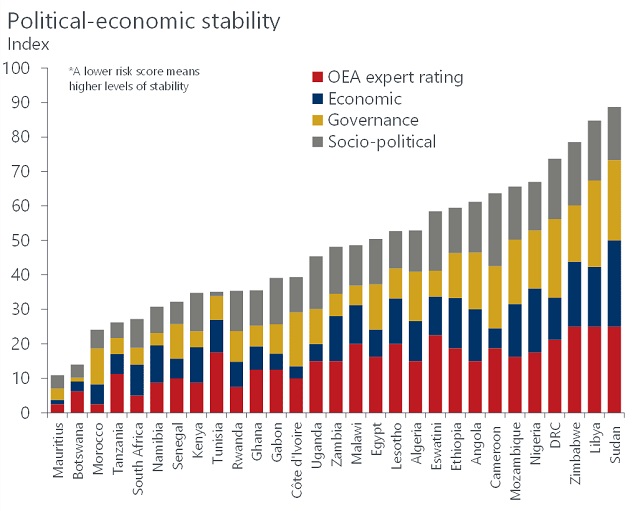

According to the researchers, political-economic stability speaks to policy predictability and consistency and is the final piece of the puzzle.

Political-economic stability is modelled by looking at the connections between the government, society, macroeconomic climate, and the operational environment, and how these interact with policy over time. Overall, Africa’s policy environment has trended more stable over the decades; however, stability risks have increased somewhat over the past few years.

“Politics and economics are inextricably linked, and this is especially true in emerging market economies and in African countries,” the Oxford report says, “Political economics helps us understand these interactions and explains the drivers and consequences of events like elections, coups d’états, and civil conflicts.”

It adds: “Furthermore, political-economic approaches are also vital to untangle the varying policy environments across the continent.”

That is why, the researchers say, they developed their framework to models the interactions between society, the government, and the macroeconomic climate and their impact on the policy environments in African countries. The policy environments of countries are mapped on two axes: political-economic competition and political-economic stability. Political-economic competition models who holds power and political-economic stability models how predictable is the policy environment.

Political-economic competition

Uganda is on the borderline of political-economic power risk. It can be viewed either as a once-promising country that has slipped into the negative completion arena together with countries like Nigeria, Cameroon, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe.

In these negative competition countries, the government’s policy powers are primarily challenged by the military or by insurrectionist groups in the country. These groups’ influences vary between countries and are measured by looking at the country’s history of conflict, the importance of the military in society and their physical and financial might, and political sway. While the extent of these groups’ influence varies, there are notable commonalities in the policy environments between these negative competition countries.

“Broadly, their policies are often geared to either appease the military or to combat an insurrectionist movement, with budgets prioritising spending on the security forces over the rest of society,” the report says, “This results in short-term focused policies, where the near-term stability of the current government outranks the country’s long-term development.”

Countries with entrenched positions in this zone include Sudan, Ethiopia, Libya, Egypt, and DR Congo.

Alternatively, Uganda can be seen as a country on the cusp of entering the positive competition zone. Countries making baby steps in this zone include Rwanda, Gabon, Eswatini (Lesotho), and Algeria. The dominant countries in the positive competition zone include Tanzania, Kenya, South Africa, Botswana, and Mauritius.

In these positive competition countries, civil society groups keep the government in check, thus gaining influence over the policy formulation process.

“The main civil society groups are strong opposition parties, an independent judiciary, an active and politically engaged population, and interest groups,” the researchers say, “We measure a country’s civil society strength by looking at education levels, civil liberties, and press freedom, as well as the quality and political power of the different consistency groups.”

They add: “While the relative power of these groups differs between countries, positive competition countries share several policy commonalities. Policies in these countries are more geared towards growth and development, political and societal inclusion, and free market economics, and are typically pro-democratic”.

Political-economic stability

The researchers model policy stability on four pillars: economic, governance, socio-political, and the Oxford Economics Africa (OEA) expert rating.

The economic pillar of policy stability looks at a country’s macroeconomic and financial climate, and how this interacts with the policy environment. This pillar is captured using macroeconomic, financial, and fiscal capacity, along with our Oxford Economics risk indicators.

The governance pillar of policy stability represents the policy development and implementation environment of each country. It is measured by looking at the country’s regime type, the government’s structure, the prevalence of political violence, and the ruling party’s legislative and political power.

The socio-political pillar of policy stability considers the interaction between the policy environment and the broader society in a country. This pillar is measured by looking at societal polarisation, economic inequality, food security, and education and poverty levels.

Finally, the Oxford Economics Africa (OEA) expert pillar is an internal and subjective score which we assign based on qualitative metrics that reflect our perceptions of the operational environment in every country.

The researchers say all countries have at least some political-economic stability risks. But some like Mauritius and Botswana have fewer risks. Secondly, in most cases, the four risk scores tend to be relatively in line, meaning that higher risk in one metric typically leads to rising risks in the other metrics.

While socio-political risks have declined slightly due to rising education levels, declining poverty, and improved social cohesion, governance and economic risks have trended higher, the researchers say to explain why political-economic stability risks have increased over the past few years.

“The largest jump occurred in 2020 due to Covid-19, with the associated increase in economic and political risks still persisting in 2022,” they say.

They combine the political-economic competition and political-economic stability axes to get the completed political-economic risk model.

“Countries with higher levels of positive competition tend to have higher levels of stability, while countries with higher levels of negative competition tend to be less stable,” the researchers say.

They add: “This fits political and economic theory, as countries with thriving civil societies that keep the government in check are more stable than those where the military plays a more active role in governance”.

The worst and the best

Based on this, countries are divided into four groups or quadrants. In the first quadrant (Q1), negative competition and stability interact. This is the worst category. Currently, no countries fall into this category, the researchers say but, historically, countries like Rwanda and Uganda been in this category.

The researchers say: In these countries, the military serves as the main check on the government’s power, which could lead to moderate levels of stability. Nevertheless, it is difficult to maintain political-economic stability in these countries, and their policy environments are generally less stable than in countries where civil society keeps a check on the government’s power.

In the second quadrant (Q2), negative competition and instability interact. Several countries fall into this category. These countries range from moderately stable (Egypt and Uganda) to highly unstable (Sudan and Libya).

The researchers say: On the policy front, these governments tend to run higher budget deficits, as funds are allocated to appease the military or to finance a domestic conflict. This can lead to rising debt levels, declining access to external funding, and fiscal policies prioritising short-term spending over long-term development. These countries are less stable, as growing societal discontent can lead to violence and protests. Furthermore, restricted access to international finance and concurrent budget deficits weaken the government’s ability to provide relief during crises, which amplify the fallout from events like floods, droughts, and disasters.

In the third quadrant (Q3), positive competition and instability interact. Five countries fall into this category: Algeria, Malawi, Zambia, Lesotho, and Eswatini. In these countries, civil society serves to restrict the government’s power, however, the countries in this category vary notably on this front.

In Eswatini and Algeria, the government’s power is markedly stronger than civil society’s, and it can act relatively unchecked compared to Lesotho and Zambia. On the policy front, these countries tend to be less resilient to exogenous shocks (compared to their Q4 counterparts), but they are far better off than those in Q2. Countries in this category are expected to have higher debt levels, below-potential economic growth, and a reliance on primary resources. Furthermore, due to higher levels of instability, short-run volatility is expected to have a more prominent impact on weakening the macroeconomic climate while also hindering development. Nevertheless, these countries have good prospects to improve over time, but uncertainty is expected to persist in the near term.

In the fourth quadrant (Q4), positive competition and stability interact. These countries have the best policy environments in the Oxford Economics model.

The researchers say: In Q4 countries, governments are held in check by civil society, opposition parties, the judiciary, and the constitution. Yet, this can range widely, from countries where the government holds most of the power (like Rwanda), to those where a vibrant civil society successfully holds the government accountable (like Mauritius).

“While policies can still diverge between the countries in this category, overall, these policies generally promote growth, longer-term development, and investment. This can become a self-sustaining system, where growth-inducing and inclusive policies lead to a more stable society, and in turn, further enhances the policy environment’s quality,” the report says.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price