A comparative look at Museveni’s economic performance against other long-serving leaders in the region

COMMENT | Alan M. Collins | The word “stagnation” often follows the word “economic”, followed by period, decline, and unemployment according the British National Corpus, which collects samples of spoken and written English. In the same way, the word stagnant is often used in reference to the Ugandan economy. However, it isn’t a completely fair term because, since Uganda negotiated a policy framework with the IMF and the World Bank in 1987, it has experienced steady, if slow, economic growth. In fact, there are only a handful of African countries that have managed to exceed Uganda’s slow climb over the period: Angola, Botswana, Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, and nearby Sudan. So why the need for the term stagnation, when the economy seems to be doing so well?

The article, ` Why the Economy Isn’t Growing Like It Used To’ by Philosophistry defines economic stagnation as, “a prolonged period of slow economic growth (traditionally measured in terms of GDP growth), usually accompanied by high unemployment”.

Before we look at the figures, it must be mentioned that economic growth is a relative term; especially considering the unique impact colonialism and imperialism have had on Uganda and other parts of the world. Economic growth is relative because the world is economically unbalanced.

So, Uganda’s meager 5% growth rate over each 5-year period of Museveni’s 30-year presidency could be seen as admirable, until it is realised that at that rate of growth, it would take an eternity for Uganda to get on equal terms and compete with the imperial powers. It’s a mathematical impossibility.

A 5% economic growth rate is simply insufficient to close the widening gap between the so-called developing and developed nations. There are indications that the economic reforms dictated by the IMF and World Bank that have aided Uganda’s growth over the past three decades have largely failed to see any developing nation transition into a developed one. While the developing nations implement reforms that see modest growth, the developed nations continue their exponential climb and continue to widen the socio-economic gap between rich and poor.

A look at the next factor for using the term economic stagnation in relation to the Uganda economy, which is GDP per capita growth, is equally interesting. This is also where things start to become either a little murkier or a little clearer, depending on which side you happen to be looking at it from.

According to the World Bank, Uganda’s GDP per capita when President Yoweri Museveni’s NRM took over in 1986 was US$258, which at the time was higher than neighbouring Tanzania, as well as Equatorial Guinea and Eritrea, among others.

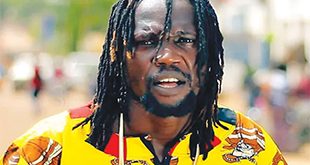

Museveni has been in power for 33 years, and if someone maintains power for a long period of time, it could actually be assumed by Western philosophy like Hobbes, Locke and Rosseau that he is fulfilling his social contract, or would otherwise be deposed. But that is not the case for Museveni. And this is an objective look at Uganda and the occasional western argument on the impact of democracy versus dictatorship on economic growth should not be applied here.

Only three African presidents have been in power longer than Museveni. They are Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea (1979-present), Cameroon’s Paul Biya (1982-present) and Congo Brazzaville’s President Denis Sassou Nguesso (1979-1992, 1997-present).

What is interesting about Africa’s longest serving president, Obiang, is that he has fulfilled his social contract by taking a GDP per capita that was lower than Uganda’s in 1979, and growing it 50 times larger over the course of his presidency. This is largely due to exploitation of the world’s continued reliance on fossil fuels. Jose Eduardo dos Santos did the same to a lesser extent in Angola to legitimise his 38-year reign that only recently ended a little over a year ago.

But the next three presidents on the list, rounded out by Museveni, have not so unquestioningly fulfilled their social contracts. Cameroon, Congo, and Chad all have long-serving presidents in charge of nations that have seen marginal growth. These presidents have only managed to double their countries’ GDPs per capita over the course of roughly 25-35 years.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price