Virologists say it’s only way out as disease won’t go away soon

Kampala, Uganda |THE INDEPENDENT | On July 30, Uganda received 286, 080 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine from Norway. On July 31 another 300,000 doses, of the Sinovac vaccines, arrived from China. Earlier Uganda had received 1,139,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccines.

All the vaccines received so far are free of charge for Uganda; funded through the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility that coordinates international resources to enable low-to-middle-income countries equitable access to COVID-19 tests, therapies, and vaccines. But that has not barred Uganda from setting very ambitious vaccination targets for itself as it follows almost all other countries.

According to the Ministry of Health, Uganda targets to vaccinate at least 50% of its population (about 22 million people). The vaccination is to be done in phases.

But at this point, only 1.1 percent of people in low-income countries like Uganda have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. And only 27.1 percent of the global population had received at least one COVID-19.

Africa which has a population of 1.2 billion people has received just 82 million COVID-19 vaccine doses.

“We all need to do more to ensure vaccines are available, and we need to do it now,” said Dag Inge Ulstein, Minister of International Development in Norway.

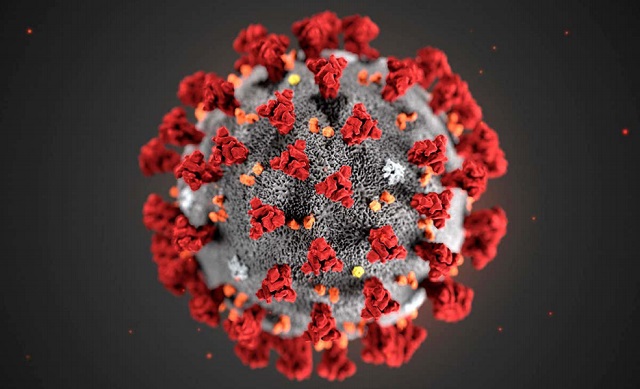

But as the race to vaccinate more and more people rages, some leading scientists are warning that the rush is misleading on two fronts; first it creates a misconception that the world will get to a stage where the SARS-CoV-2 virus which causes Coronavirus disease or COVID-19 will be eliminated. Secondly, that if enough people are vaccinated, the world will attain herd immunity; a situation where the immunity in the population against infection by the virus is such that there are too few people in the environment for sustained onward transmission to take place to others. In other words, herd immunity is when someone infected by the virus won’t, on average, be able to infect another person.

This is because they’ve developed immunity against being infected, or at least have developed immunity to the extent where even if they were infected, they would be able to clear the virus very quickly and wouldn’t be able to transmit it to other people.

So herd immunity essentially means that you have brought about an absolute interruption in the chain of transmission of the virus in the population in the absence of other interventions that too could interrupt virus transmission such as wearing of face masks.

Thinking has changed

But some experts say changes have forced a shift in the thinking among scientists about herd immunity. “It’s now viewed much more as an aspiration rather than actual goal,” says Prof. Shabir A. Madhi, the Director of the SAMRC Vaccines and Infectious Diseases Analytics Research Unit, University of Witwatersrand in South Africa.

Prof. Shabir A. Madhi, who is the Dean Faculty of Health Sciences and Professor of Vaccinology at the university, says several things have changed and caused a change in opinion regarding herd immunity.

According to Madhi, the first, major change has been the evolution of the virus and the mutations that have occurred. One set of mutations made the virus much more transmissible or infectious. The Delta variant is just such an example.

Initially scientists thought the SARS-CoV-2 reproductive rate was between 2.5 and 4. In other words, the scientists thought, in a fully susceptible population every one person infected would on average infect about two and a half to four other people. But the Delta variant is at least twofold more transmissible. That means that the reproductive rate of the Delta variant is probably closer to six rather than three.

The second change is that the virus has shown an ability to have mutations that make it resistant to antibody neutralising activity induced by past infection from the original virus, as well as antibody responses induced by most of the current COVID-19 vaccines.

The third big issue centres on the durability of protection. According to Prof. Madhi, the memory responses induced by past infection are lasting for at least six to nine months at the moment. But that doesn’t mean that they will protect us against infection from variants that are evolving, even if such memory responses do assist in attenuating the clinical course of the infection leading to less severe COVID-19.

The fourth issue conspiring against the world being able to reach a herd immunity threshold any time soon is the inequitable distribution of vaccine across the world, the slow uptake, and the sluggish rollout. Unfortunately, this provides fertile ground for ongoing evolution of the virus.

No country is going to lock its borders perpetually. This means the entire global population needs to reach the same sort of threshold round about the same time.

“With the Delta variant, we would need to get close to 84% of the global population developing protection against infection (in the absence of non-pharmacological interventions) in as brief a period of time as possible,” says Madhi.

At the moment just 1% of the populations of low-income countries have been vaccinated. And 27% of the global population.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price