By Bob Kasango

Such attacks show why the world must widen the frontiers of freedom and promote democracy

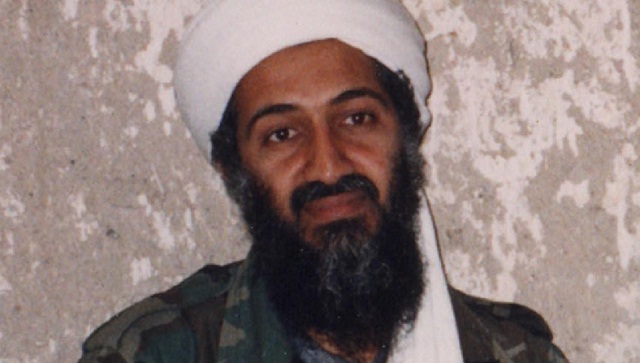

In May 2011, soon after the killing of the leader of Al Qaeda, Osama Bin Laden, in Pakistan by US Special Forces, the Economist Magazine ran a special feature titled, “Now, kill his dream”. The magazine declared that, “Osama bin Laden’s brand of brutal jihad is losing its appeal in the Arab world”. Like the Economist, various publications around the world led with triumphant headlines and some even predicted the “end of Al Qaeda”.

Other analysts received the news with cautious jubilation. President Barrack Obama of the U.S., the man who ordered the killing of Bin Laden was quick to warn that, “… violent Islamism is still a dangerous force. Al-Qaeda is active, even without Mr Bin Laden.”

The Economist went on, “the task now facing all those who yearn for a safer world is to isolate Mr. Bin Laden’s savage jihad just as surely as its creator was isolated behind his compound walls”.

Before and after the death of Bin Laden, most of the leading figures in the Al Qaeda hierarchy had and have been «eliminated», but each time they killed one, another sprung up and was sometimes more violent and militant. These developments soon proved that jubilation may have been too much too early and that there is so much more to be done in the fight against violent jihad and international terrorism.

What happened in the upscale Westgate shopping Mall in Nairobi Kenya on Sept. 21 is a stark reminder to the world that ancient hatreds and prejudices still haunt our new world. The world became a very different place since 9/11 and so conversations that will take place after Westgate will be of even greater importance.

The real reason the terrorists attacked Westgate, we may never know and there will be many explanations. May be they saw it as symbol of «Zionist western civilization» and corrupt materialism. Judging from the dead, injured and traumatised at Westgate, it represented, to some of us, a world of growing diversity, expanding freedom and opportunity, and a deep sense of mutual respect for a genuine community. The terrorists described themselves as «Islamic jihadists», but many Muslims died at Westgate. So why do the violent jihadist terrorists hate a world of expanding communion and freedom?

To make sense of all this, it is important that we have a clear understanding that we and the perpetrators of terror and their supporters have very different notions about the most important things in life – the nature of truth, the value of life, the content of community.

The Al Shabaab and their ilk actually believe they have the truth. To them, the world is divided between those that share their truth and those who do not. The Muslims who disagree with them, like my Westgate hero – Abdul Haji, a civilian Kenyan-Somali Muslim who took on the terrorists and saved many innocent lives, are heretics. The non-Muslims are infidels – kafir. And if you do not share their truth, then your life doesn’t count and you are a legitimate target.

But the limits of human nature prevent any of us from knowing the whole truth.

To the terrorists, community is a group of people who think alike, look alike, dress alike, act alike. They believe in a community whose rules are enforced brutally, women should not go to school, are imprisoned behind their burkas and veils by men who beat them in public, paint their windows black to make sure they do not see the world outside and even shoot them when they leave home without permission.

By contrast, the community they attacked is one in which we all do better when we live together and accept the simple rules of engagement because everybody counts, everybody deserves an equal chance, and every life is important.

The terrorists believe what is important about life is our differences.

The great advances in science and technology in the 21st Century also make a compelling case for what happened at Westgate and expose the dark side of the interdependent age in which we live. We have torn down walls, collapsed distances, and spread information. We just could not have done all this and reaped the benefits without rendering ourselves vulnerable to the forces of hatred and destruction.

Terrorists cannot build anything. Indeed they get their foot soldiers and sympathisers largely from ranks of frustrated people who feel trapped in failed societies.

Many years back I had a debate with some friends, including Andrew Mwenda over the events then unfolding in Somalia. I believed then as I do now that a robust intervention force was required to bring order to the country. My friends did not agree.

Andrew Mwenda like many other political thinkers held the view that Somalia should be left to self-destruct. With the eventual implosion, it was argued, the Somalis would come to their senses and reach an internal consensus to stop war and rebuild the country.

We all know what became of Somalia when the world left them alone. But for countries like Uganda, Ethiopia, the United States of America and Kenya, even the fledgling semblance of sanity that there is in Somalia today would not be.

Of course our debate over Somalia was prior to 9/11. Most if not all of my protagonists then have changed their positions principally because the world is a different place now.

But why do terrorists still have these recruiting grounds despite the democratic transitions and consolidations since the end of the Cold War? Why do these people kill others so senselessly? Why do terrorists hate peace? Why do some people believe in some ideals so strongly that they are willing to kill for them?

Although many people today believe that religious fanaticism “causes” terrorism, I disagree. It may be true that religious fanaticism creates conditions that are favorable for terrorism. But we know that religious zealotry does not ‘cause’ terrorism because there are many religious fanatics who do not choose terrorism or any form of violence.

Terrorism is a tactic of extremists within each religion, and within secular religions of Marxism or nationalism. No religion, including Islam, preaches indiscriminate violence against innocents.

In the 20th Century, of the estimated (and this is hardly a firm figure, understated if anything) 120 million people who were killed in wars and war-like acts (terrorism is war, generally upon civilians, by a non-nation-state) only a small fraction of that figure was the result of Muslim killings.

It takes a peculiar sort of blindness to see Christians as “nice” and Muslims and inherently violent, given the twentieth century death toll I mentioned above.

People resort to violence out of ambition or grievance, and the more powerful they are, the more violence they seem to commit and the less we confront their ills, the more emboldened they get. And Christians are as guilty.

On Sunday September 21, the day after the Westgate attack, a violent extremist suicide bomber killed 85 Christian worshippers in an Anglican Church in Peshawar, Pakistan. Despite a higher death toll than Westgate, and an even more gruesome nature of the killings, the international media gave the incident lukewarm attention and I have not met anyone that has anything to say about that massacre in Pakistan! Why?

In this war on terrorism, we must remember that terrorism anywhere is ultimately terrorism everywhere. We embolden the terrorists when we stay silent in the face of their actions.

So there must also be other conditions that in combination provoke some people to see terrorism as an effective way of creating change in their world.

Let me attempt to offer one why reason why by statistical example – an estimated hundred million children in the world today are not in school. Half that number is in sub-Saharan Africa, 25% on the Indian subcontinent, and 25% in East Asia. This has some tragic consequences.

In 2003, a television documentary showed an 8-year old Pakistani boy who could recite the Quran back to back by heart, but he could not answer the question what is two times two. He said it was impossible that anyone had ever walked on the moon. He then said that there were still dinosaurs on the Earth and that they had been put there by Americans and Zionists to kill Muslims.

In the same documentary, there was a ten-year old boy who said he would be happy some day if he could die killing Americans. He said the only country he wanted to visit was Afghanistan, and the only person he ever wanted to meet was Osama Bin Laden.

These children become fanatics because those of us that believe in a safer more decent interdependent world do not help them have a decent school that gives a child an education that makes them useful. We have let them organise their world in differences; blacks and whites, men and women, Christians and Muslims, Jews and Arabs, them and us. Because we are absent, the violent extremists take our place, the place of governments, the place of the international community and indoctrinate these young children.

The Index of Economic Freedom, by the Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal, concluded that, “Economically free countries exhibit greater tolerance and civility than economically repressed ones, where hopelessness and isolation foment fanaticism and terrorism”.

The world’s largest concentration of economic repression—Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, Mali, Iraq, Syria and Libya—is also a primitive hotbed of terrorism. Egypt, Sudan and Yemen are “mostly unfree” and are all so void of a rule of law that they are impossible to analyse.

The world must therefore do more to widen the frontiers of freedom and promote democracy. We need to be sensitive about the economic and political challenges certain countries face. The world should never turn a blind eye when states fail or seem to do so like we did in Somalia for far too long.

*****

The writer is a Kampala lawyer

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price