Museveni defends, Buganda reacts

Kampala, Uganda | MUBATSI ASINJA HABATI | On 10 February 2022, the Minister of Finance, Matia Kasaija signed an agreement with an Italian, Enrica Pinetti to allow her company, Uganda Vinci Coffee Company Limited (UVCC), to establish a coffee processing plant worth US$80 million.

Apart from the involvement of Enrica Pinetti, an already controversial Italian in Uganda’s foreign investment circles, the overly generous terms of the agreement have left a bitter taste.

A deeper investigation by The Independent shows, however, that the furore over the Vince deal could offer new understanding for Ugandan coffee farmers into how the international coffee market really works; its challenges and opportunities.

The Vince deal was mooted about 10 years ago.

In May 2014, at a meeting with President Yoweri Museveni at his Rwakitura country home, Pinetti impressed him when she roasted coffee seeds using a mini roaster and made the President taste different delicious samples.

Pinetti assured Museveni that her factory would roast, manufacture, and pack instant coffee for export and the local Ugandan market.

“I have spent a very long time trying to get somebody to add value to our coffee, Uganda has been a donor by exporting raw coffee,” Museveni said excitedly.

That is when Museveni pledged to provide the Italian “with all the necessary assistance to ensure that the project takes off soon”.

But eight year down the road, the factory has not gone beyond the ground-breaking ceremony and has lain in limbo.

Its recent resurrection could be tied to Uganda’s abrupt announcement in February that it was pulling out of the International Coffee Organisation (ICO) which administers the International Coffee Agreement (ICA), an important instrument representing 98% of world coffee production and 67% of world consumption.

While announcing its withdrawal, the Uganda Coffee Development Authority (UCDA) gave seven reasons including unfair tariffs, restrictions on exporting processed coffee and an “unjust and outdated” coffee classification system.

Museveni’s insistence on the Vinci deal in spite of opposition from parliament, coffee famers, traders and processors, could be down to the President’s determination to see that “Uganda stops donating the value of its coffee”.

Museveni impatient

Uganda is the 8th leading coffee producers in the world according to World Atlas.

Coffee in Uganda is not a large estate plant. It is grown on mainly small privately-owned holdings, mainly in central Uganda. But governments have over the years tried to regulate its marketing with mixed success.

Under President Museveni, the government of Uganda has pursued a multi-pronged strategy around coffee. It has sought to increase production, diversify the growing areas beyond the central region, ensure quality, and lately; regulate its sale; especially the export element.

The government has been pushing the 2018 Coffee Bill in parliament. But the Bill has run into trouble over some of its provisions and is still on the floor of parliament over harmonisation of controversial clauses. The government has, for example, sought powers to arrest farmers who do not take proper care of their coffee gardens.

Last year Uganda exported 6.55 million bags of unprocessed coffee beans worth $657.23 million. That is 0.6% of the $102 billion which the world coffee business accounts for globally.

For decades, many commentators have argued that Uganda could earn more from its coffee. But for that to happen, Uganda needed to have exported processed coffee and not raw beans.

Yet Uganda has continued exporting raw coffee beans to Europe just as the colonialists designed it to be.

This is the argument the UVCC or simply Vinci, a private and until recently unknown company, reportedly used to convince officials at the Ministry of Finance to get government backing.

Vinci sold the idea of buying Ugandan coffee, processing it, and then exporting it.

The question is why is it so difficult for Uganda, or many African countries for that matter, to develop capacity to process its coffee and penetrate the market from farm to coffee cup?

While responding to its withdrawal, the ICO said Ugandan concerns, including barriers to exporting “value-added” processed products, are currently under review by a working group established in 2019 to update and reform the current Agreement.

While referring to its 2020 internal report which found that processed coffee imported from Uganda is subject to a 60% tariff while other countries, including European Union, Norway and Japan, pay low or zero rates, the ICO said “the unbalanced tariffs are an ongoing concern in the global coffee market”.

The ICO added that tariffs are under the jurisdiction of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

It appears President Museveni has grown impatient and is eager to see major economic gains from the effort his government has recently invested in coffee.

Defending the deal

Defending the deal with Vinci, Ministry of Finance Permanent Secretary, Ramathan Ggoobi, said the Government, through Operation Wealth Creation has invested heavily in promoting coffee production through among other things providing improved seedlings.

“The stated aim is to push the current annual production of 420,000 tons up to 1.2 million tons in the year 2030,” Ggoobi told Parliament, “We want to produce more coffee, and get the best out of it. We’re targeting $2 billion.”

He mentioned partners in the ambitious undertaking, such as the Buganda Kingdom.

“The win-win solution for everyone is for us to produce more coffee, and ensure that most of it (if not all) is premium. That is a good challenge to have. Otherwise how can it be that out of the 420,000 tons of coffee we produce today, only 60,000 tons would be premium? In guaranteeing supply of premium coffee to Uganda Vinci, the Government undertook to take “reasonable” steps. Such steps cannot include blocking other investors from honouring their agreements.”

Ggoobi argued: “If we can process our coffee to fine, finished products, we can get nine times more monetary value out of it i.e. $5.4bn a year. In addition, we would get more of our people employed in the coffee chain here at home, among other advantages.”

Ggoobi told MPs that Vinci is the investor that came forward with a plan to do what the government wanted to be done. He said they offered to invest $80m to process coffee in Uganda, and then sell it in virgin markets in Europe and elsewhere.

“The cost and risk of penetrating those virgin markets are for Vinci to shoulder. All the Government has done is to provide Vinci with a measure of incentives that are available to every strategic investor – in coffee, dairy, iron and steel, name it,” he said.

According to Ggoobi, the incentives offered to Vinci should not be an issue because they have been offered to other investors – local or foreign.

He said in any case, they are only for the first 10 years.

He said: “It is just to help it lay a foundation. Government has done the same to so many other businesses that have played a role in Uganda’s development. After Vinci has penetrated the virgin markets and starts making profits, the incentives we are discussing will no longer be available to it, and it will pay all the taxes due to the Government. This is the plan for all investors who get incentives.”

Complex problem

But Ggoobi, it appears, had deliberately chosen to simply a complex situation which poor coffee producing countries continue to battle against as they attempt to get more money from their produce in the international coffee value chain.

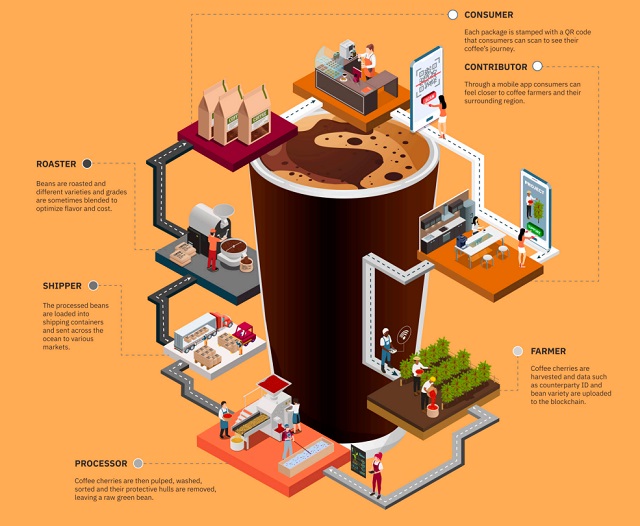

The coffee supply and value chains are complex. They involve highly scrutinised activities from growing, harvesting, transporting and shipping, processing, milling, roasting and packaging. Poor farmers in over 80 countries in Africa, Latin America, Asia, and India grow the crop while fewer countries in the rich process, roast and package. The poor fight to go into roasting and packaging but the rich, through organisations like the ICO and WTO, ensure they cannot.

It has been documented that the African farmer produces some of the finest coffee beans but receives the lowest prices of all growers, globally. That African coffee farmer is losing $1.47 billion every year from exploitative pricing of their crops. That due to unfair trade terms, in Africa’s biggest coffee producers; Ethiopia and Uganda, coffee farmers are estimated to lose US$713.1 million and US$229.7 million every year.

As a result, millions of Africa’s coffee farmers have slipped into abject poverty caused by poor prices which are currently barely enough to cover production costs while the rest of the coffee supply chain players enjoy rising profits.

These statistics are contained in a report title `Misery at the Farm: Africa’s Coffee Farmers are Losing Billions to Exploitation’. The report says the share of an African farmer in the roasted coffee value chain is ranging from 8.7% to 12.6%, with the share being less in major African coffee exporters, Ethiopia and Uganda, being respectively at 12.6% and 10.0% respectively. Farmers’ shares in the roasted coffee value chain are higher outside of Africa with India’s coffee growers getting 15.7% in India and 14.9% in Brazil.

“These amounts are crucial for African producers from several countries where coffee is their major exporting product,” the report said.

The report was released in 2020 by Selina Wamucii, a platform for food and agricultural produce from Africa’s agricultural cooperatives, farmers’ groups, agro-processors, and other organisations that work directly with family farmers across 54 African countries.

The grim fact by Selina Wamucii and others, and his lived reality in Uganda are perhaps why President Museveni described thoe opposed to the Uganda-Vince deal; with its potential of adding value to Ugandan coffee, as “agents of foreign interests”.

“This is a struggle between the comprador bourgeoisie, the agents of foreign interests, and the local bourgeoisie,” Museveni said while officiating at the May 01 Labour Day celebration in Kampala.

Many still unhappy

At its latest sitting, the Lukiiko Parliament of the Buganda kingdom criticized the Uganda-Vinci agreement and pledged to host a grand meeting of all major coffee producers in the country.

Buganda has a big stake in the coffee sector in Uganda.

The country produces mainly Robusta coffee (85%) and Arabica. Up to 80% of Robusta coffee is produced in central Uganda which comprises mainly Buganda.

According to the kingdom officials, the Uganda-Vinci deal should be cancelled because it will not yield anything developmental and could be detrimental.

According to the deal Vinci got, the coffee company would retain exclusive rights to buy all Uganda’s coffee. This agreement also offers UVCC a 10-year tax holiday, waivers on power tariffs and constant water supply, among others.

Coffee farmers have urged parliament to cancel the agreement between the government and Uganda Vinci Coffee Ltd. They say it infringes on the law. Appearing before the parliamentary trade committee, the farmers say that it is unnecessary to contract a foreign firm to carry out value addition because they can do it if supported like Vinci.

The investigations

On April 25, 2022 the Parliamentary Committee on Trade, Tourism and Industry commenced investigations into the controversial coffee deal signed between Government and Uganda Vinci Coffee Company Limited (UVCC). The Committee sought to question Enrica Pinetti, the controversial and elusive board chairperson of Vinci. But the Italian snubbed parliament by not appearing before the committee.

Moses Matovu who signed the agreement as Vinci’s company secretary, Ramathan Ggoobi, the Secretary to the Treasury, and Finance Minister Matia Kasaija signed on behalf of GoU appeared before the Committee.

The MPs were peeved when Moses Matovu told them that Pinetti, who was present at the coffee processing agreement signing in February, could not show up before their committee because she was with President Yoweri Museveni at the time. Many MPs accused Museveni of sheltering Pinetti. They rescheduled her appearance. But she snubbed them again.

Pinetti is not new to controversy in Uganda. In 2018, she under a company named Finasi, secured the backing of parliament to fund the construction of the Lubowa Specialised Hospital. Controversially, the government issued a promissory note, promising to pay up to US$397 million to the Italian firm Finasi, as long as the company built the hospital. The hospital construction was supposed to be completed within two years but four years later there is not much to show.

Again, at that time, many people questioned why the government was propping up a foreigner who clearly had neither money, nor expertise in the hospital business.

“Vinci is owned by powerful Ugandans who are using Pinetti as a front,” said MP Samuel Ssemakula Lutamaguzi (Nakaseke South).

In the Coffee deal case, the Committee chaired by MP Mwine Mpaka (Mbarara City), said they had unearthed irregularities.

During the meeting, while interrogating officials from UVCC led by the company secretary, Moses Matovu, MPs were dismayed to learn that Pinetti, as director of UVCC had sought to mortgage the 25 acres of government land she had been given free of charge in Namanve Industrial Park near Kampala to secure a loan from a commercial bank. The Italian claimed she would use the money to set up the coffee processing plant.

An email reportedly written by Pinetti in 2018 to Uganda Investment Authority (UIA) states that Vinci had wanted to use the 25 acres given to it in Namanve to secure a loan from a bank. Vinci planned to use the loan to establish and operate an integrated roasting, grinding and instant coffee processing plant.

The MPs wondered why Vinci which had benefited from a free land and a waiver of premium which would amount to about US$2 million, request to mortgage the same land. Pinetti was stopped in her tracks because, according UIA Executive Director Robert Mukiza, for a foreign investor to be allowed to mortgage a UIA land title to acquire a commercial loan, they are required to have constructed the factory to 60 per cent completion. Vinci had not yet even gone passed ground-breaking for the factory.

Government has no coffee

Many people believe this agreement in its current form alienates Ugandans from the coffee business as it gives monopoly of purchase and export of coffee to only one organisation.

The agreement exempts the coffee company from paying all the taxes, including Income Tax, Pay As You Earn, Excise Duty and National Social Security Fund and also seeks to subsidize the company, giving them a special tariff in terms of electricity contrary to the Coffee Act.

But the Attorney-General, Kiwanuka Kiryowa and Finance Minister Matia Kasaija have defended the controversial coffee agreement between the Government and Vinci.

Kiryowa told MPs investigating the coffee deal that Vinci’s contract with government contract is essential to promote value addition to coffee after Uganda withdrew from the International Coffee Organisation.

“I checked the company’s legal standing and I was convinced that the company has proper legal standing in Uganda, therefore the contract has no breach of any provisions of the law. So, I confirm that I carried out legal due diligence on the company and I am convinced it is in compliance with the provisions and any of the laws,” the Attorney General said.

On his part Kasaija defended the agreement arguing that Ugandans will benefit.

“This agreement does not deter other potential investors from investing in value addition; UVCC provides an opportunity for the country to fetch better prices for high grade coffee. The company aims to establish several hubs across the country intended to enhance traceability of farmers and to eliminate middlemen,” Kasaija said, adding that UVCC will pay a competitive and market determined price.

Bwamba County MP, Richard Gafabusa, questioned why Government did not consult widely before signing the controversial coffee contract. He also wondered why there was no termination clause in the contract that was signed with UVCC.

“Enrica acquired the deal to get the land but over the years nothing has been done. Over 10 years have gone by and the deal has just been finalised this year. This makes the previous years null and void. Is there any clause that calls for termination in case the investor fails to deliver?” Gafabusa asked

“Coffee is not a natural resource that is owned by the Government; and since the company does not have coffee, our farmers shall also not be party to their agreement because they were not consulted,” Amuria Woman MP, Suzan Amero said.

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price