World Bank, BoU explain short-term, long term opportunities, challenges

Kampala, Uganda | AGENCIES | The outlook for long term economic growth is positive but a lot of drag persists in the short term. Viewed that way, the latest World Bank outlook for Africa matches the sentiment of the latest outlook of the Uganda central bank announced on April 06.

The Bank of Uganda Monetary Police Statement for April said economic growth remains on a recovery path but it projected that it would remain below its long term trend until FY2025/26 because of tight domestic and external financial conditions.

The BoU statement singles out inflation, expected increased pressure on the Shilling, lower export to import prices, slower growth of export volumes, and lower than expected global growth outturns.

The BoU statement is mirrored in a similar report released in the same month by the World Bank on the Economic prospects for Africa.

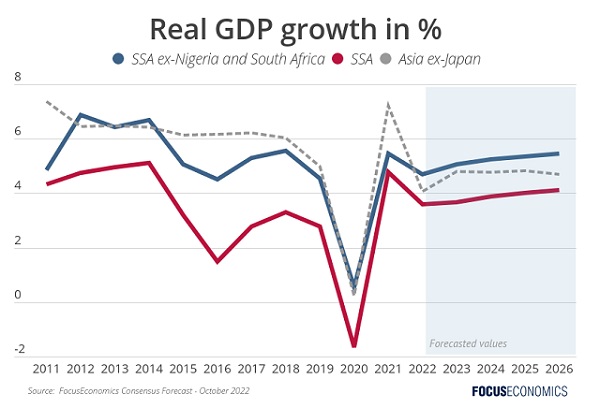

Dubbed `Africa’s Pulse’, the World Bank’s April 2023 economic update says growth on the continent, excluding large countries such as Angola, Nigeria, and South Africa, is projected at 4.3 per cent in 2023 and set to expand to 5.1% and 5.2% in 2024 and 2025, respectively.

Taken together, however, growth for the big and small economies of Africa is set to slow down from 3.6% in 2022 to 3.1% in 2023 but will bottom out and rise to 3.7% and 3.9% in 2024 and 2025, according to the new report. That projection mirrors the BoU growth outlook for Uganda.

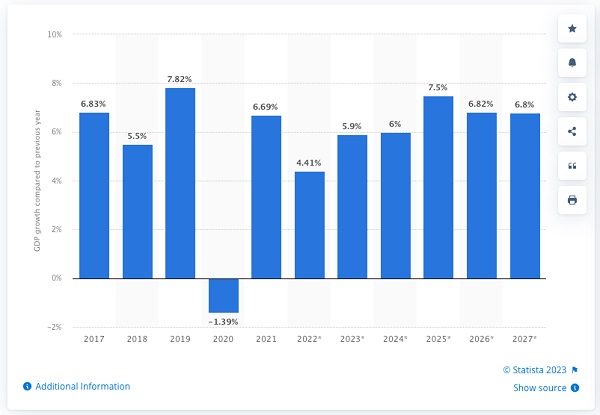

The World Bank report does not mention specific figures for Uganda but the BoU April Monetary Policy Statement figures project the economic growth in the 5.5 -6% range for FY2022/23. It says the moderation in growth partly reflects the tight monetary and fiscal policy, as the increase in domestic interest rates and tight credit standards by banks affected growth in private sector credit.

The BoU statement says the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) assesses that the near-term risk to the inflation outlook remains elevated with considerable uncertainty surrounding the economic outlook.

That sentiment is similar to that of the World Bank’s April 2023 economic update which attributes the growth deceleration partly to high inflation.

“Stubbornly high inflation and low investment growth continue to constrain African economies. While headline inflation appears to have peaked in 2022, inflation is set to remain high at 7.5% for 2023, and above central bank target bands for most countries,” the report said.

Other factors affecting the continent’s growth rate include the slowdown in the global economy, and the underperformance of the continent’s largest economies.

In Eastern and Southern Africa, economic activity is expected to grow at 3.0 per cent in 2023, down from 3.5 per cent in 2022, but to accelerate to 3.7% and 3.9% in 2024 and 2025, respectively. The economic performance of the sub region is dragged down by the underperformance of two of its largest economies, South Africa and Angola.

“In South Africa, economic activity is set to weaken further as structural constraints particularly, the energy crisis and headwinds persist. Growth will decelerate to 0.5 percent in 2023 (from 2.0 percent in 2022), and it is expected to rebound to 1.3 percent in 2024 and 1.6 percent in 2025,” writes the report’s authors.

Excluding South Africa and Angola, the Eastern and Southern Africa sub region is expected to grow at 4.4% in 2023, and is set to speed up to 5.1 and 5.3% in 2024 and 2025, respectively.

In Western and Central Africa, economic activity is expected to grow at 3.4% in 2023, down from 3.7% in 2022, and accelerate to 3.9 and 4.0 per cent in 2024 and 2025, respectively. The economic performance of the sub region has been dragged down by Nigeria its largest economy.

“The Nigerian economy is set to grow by 2.8 per cent in 2023, down from 3.3 per cent in 2022. It is expected to accelerate slightly to an average annual rate of 3 per cent in 2024–25.”

Economic activity in the sub region excluding Nigeria is set to grow 4.2% in 2023, rising to 5.3% in 2024–25.

In North Africa, double-digit food price inflation will weigh on the region, causing growth to slow to 3% in 2023 after growing 5.8% in 2022.

“Developing Oil Importers in the region, including Djibouti, Morocco, Egypt and Tunisia, grappled with the double hit of high oil and high food prices both of which they import and grew very little. The exception is Egypt, which outpaced other oil importers,” the World Bank noted in its Middle East and North Africa update.

World Bank economists expect that developing oil importers will grow on average by 3.6% in 2023 and 3.7% in 2024. These projections reflect moderately high growth forecasts for Egypt, expected to grow at 4.0% in both fiscal years 2023 and 2024.

Relative to other developing oil importers in North Africa, Egypt’s forecast reflects the expectation that its competitiveness might be increased due to the recent depreciation of the Egyptian pound, growth in the services sector (mainly tourism and Suez Canal activity) and construction, which will sustain growth.

Excluding Egypt, other developing oil importers are forecasted to grow at lower levels at 2.8% for 2023 and 3.1% in 2024.

Resilient economies

Despite these challenges, many countries in the region showed resilience amid multiple crises.

In Kenya, growth of economic activity remained solid at 5.2% in 2022, thanks to strengthened manufacturing, improved investor confidence, and a more general improvement in risk appetite.

Côte d’Ivoire’s economy grew 6.7%, driven by private consumption, shielded from inflation through increased public wages and public investment. Industry and services were the main engines of growth on the production side.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, growth accelerated to 8.6% in 2022 from 6.2 per cent in 2021. The mining sector particularly copper and cobalt was the main driver of growth due to an expansion in capacity and a recovery in global demand.

Growth in Niger is expected to have jumped by 10.1 percentage points to 11.5% in 2022 on the back of expansion of the agriculture sector after a severe drought that dragged down growth in 2021. Investment in several infrastructure projects, particularly the construction of the oil pipeline and the Kandadji Dam, boosted growth on the demand side.

Namibia’s economic activity increased to 3.5%in 2022 from 2.7% in 2021. The growth acceleration occurred due to strong mining particularly increased production of diamonds, copper, and uranium.

Similarly, economic activity accelerated in Mauritius and Mozambique by 8.3 and 4.1 percentage points, respectively, in 2022.

Growth in Mozambique stemmed from increased coal and aluminium output, thanks to high global demand, high prices, and the start of liquefied natural gas exports to Europe, while Mauritius benefited from the recovery in tourism.

The Challenges

The report says access to energy is one of the most profound development challenges Sub-Saharan Africa faces. In 2022, 600 million people in Africa, or 43 percent of the continent, lacked access to electricity. The vast majority of them 590 million or 98 percent were in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This has left the region far behind achieving United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 7 to “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”.

Africa’s rapidly growing population has translated to energy demand increasingly outstripping supply.

“At present, Africa has 18 percent of the world’s population but less than 6 percent of global energy consumption,” the report notes.

It says the challenges are mounting alongside Sub-Saharan Africa’s population growth rate the region is growing at a rate of 2.7 percent per year which is more than double South Asia (1.2 percent) and triple Latin America (0.9 percent).

“There is a need to develop and scale up diversified energy sources to keep pace with population growth. By 2050, Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is forecasted to reach 2.5 billion, or one-fourth of the global population. By 2100, Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is expected to increase to 4.3 billion.

At present, almost half of all Africans without access to electricity live in a handful of countries the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda. Four of these countries are among the fastest growing countries in the world. Other countries are on track to achieving full energy access by 2030, including Ghana, Rwanda, and Kenya.

By 2100, the population of Tanzania is forecasted to increase by 378 percent, the Democratic Republic of Congo by 304 percent, and Ethiopia by 156 percent. Nigeria, already the most populous country on the continent, will surpass the United States to be the third most populous country in the world.

Resources versus poverty

The report says that today there are markedly more resource-rich countries in Sub-Saharan Africa than there were at the turn of the 21st century, and the number is trending even higher because of new discoveries every year.

But by 2030, it is projected that more than 80 percent of the world’s poor will be in the Africa region, and almost 75 percent of the world’s poor will live in resource-rich countries.

“As a result, global poverty eradication is becoming disproportionately a challenge faced mostly by resource-rich countries in Sub-Saharan Africa,” the report says.

Uganda is listed among the resource-rich countries. It is a fossil fuel rich country. And it is among the Sub-Saharan African countries with large reserves of resources such as oil, gas, and minerals, but the region are struggling to convert this wealth into sustainable prosperity.

By one definition, the number of resource-rich countries rose from 18 of 48 before the most recent commodity price boom from 2004, to 26 of 48 countries by the end of the boom in 2015.

This means that the majority of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa can be categorised as resource rich, with more on the path to reaching this status given two decades of major new discoveries. This trend was caused by a combination of new discoveries, new production, and rising resource prices that pushed up levels of resource abundance and resource dependence and pulled more countries into this resource-rich grouping.

Despite abundance in subsoil assets, harnessing them for sustainable development means production should not come at the cost of other forms of natural capital like forests, cropland, and biodiverse ecosystems.

The key tenet driving economic sustainability from resource wealth is to use the opportunity created by a boom to promote a more diversified economy. Although many countries actively pursued diversification strategies during their respective resource booms, the record of success is poor. For example, Chad and Sudan saw increased export concentration, while Tanzania and Uganda were able to diversify exports.

The report urges African policymakers to restore macroeconomic stability, deepen structural reforms to foster inclusive growth, and implement policies that seize the opportunities available during the transition to low-carbon economies.

“Rapid global decarbonisation will bring significant economic opportunities to Africa. Metals and minerals will be needed in larger quantities for low-carbon technologies like batteries and, with the right policies, could boost fiscal revenues,” said James Cust, World Bank Senior Economist, according to a story by the bird news agency.

He added that it would also increase opportunities for regional value chains that create jobs and accelerate economic transformation.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price