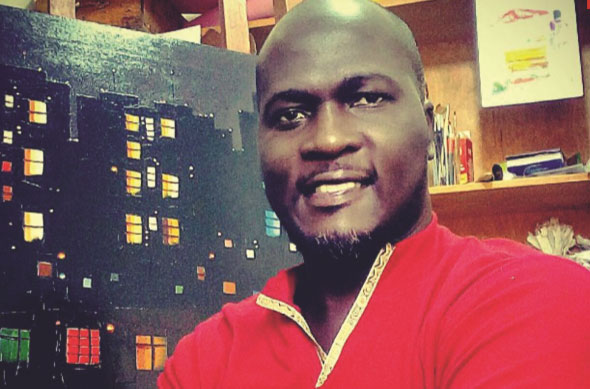

Kampala, Uganda | THE INDEPENDENT | Cliff Kibuuka is known for his startling images of Kampala landscape; especially Kampala under night- fall with the dimming light illuminating compacted settlements. Dominic Muwanguzi interviewed him on what these motifs mean and his recent work.

You document Kampala city landscape: the shanty and compacted housings, the monumental buildings like the old Kampala mosques and the clear skyline. How important is archiving in your art?

There is need to preserve this identity of the city for the future generation to see how Kampala looked like before. Similarly, my recent work includes a specific concentration on cloud formation that has been absent in my previous artworks. The reason for this inclusion is to inspire the concept of the unique Kampala skyline that I believe is spectacular and cannot be found anywhere else. I capture this as a way of documenting the character of the city that is fast transforming.

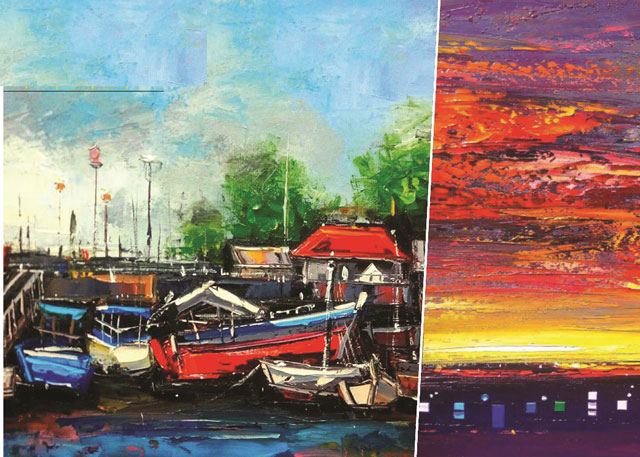

Your recent art includes regional or European sceneries like Lamu and Norway respectively. What fascinates you about these places?

They carry a special identity in terms of originality and the historical heritage. Lamu is a small town along the East Africa Coast that has maintained its Arabic culture, architecture and primal activity of fishing with dhows; not to mention the sedated lifestyle along the Island. On the other hand, Roros, a small Norwegian town, is traditionally known as a mining town inhabited by diminutive humble settlements that remind visitors of the size and character of the miners from yester-year. Incidentally, both towns- Lamu and Roros- are UNESCO world heritage sites, and I find it critical to document their traditional personality in my art.

You print your artworks on a specific type of paper. Is this in way experimental or it’s for aesthetic reasons?

The idea to print on etching rag paper was suggested by a Norwegian friend of mine who is a specialist in the discipline of printing artworks on unique paper. I then realised that I could benefit from it firstly, to create an alternative for those who want to buy my art, but cannot not afford the original artwork; secondly, to undercut the idea of commercialisation of my practice- this is important because, the way I work, I am more conceptual in my approach: I spend more time working on one piece. This means that I will supply less to the market, and yet my audience may be yearning for more. Lastly, I am able to preserve a special painting that I may never be able to reproduce.

What is your palette about and how effective is it to evoke the narrative you want to pass on to your audience?

I use oils alongside a palette knife to achieve sharp or strong contrasts in my paintings. They’re obviously difficult to work with- building one layer onto another, and it takes long to dry – but it is crucial to reveal the way I feel about a specific subject matter and to showcase the special attribute embedded in it. Here, the viewer is able to realise that the pigments are strong: a yellow is a yellow and a blue is a blue. There’s no room for mediocrity.

The art you produce is obviously familiar to the local audience because it involves indigenous art motifs. Do you feel this draws you to the average Ugandan on the street or you are still grappling with the issue of identity as an artist who is creating art to be consumed by white expatriates and not your own?

It is difficult for me to have an audience in mind when I am working, because I work conceptually. This means I paint what I feel inside and not necessarily to capture the attention of the average person; although I must say, it is important to engage them on issues that are at hand. This explains why I have been able to cross over to other spaces like Norway or Lamu. I am not essentially looking forward to have my work draw me to the local masses, but to interrogate or document the historical and cultural aspects of these specific sceneries.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price