How and why the NRM government sold Uganda’s economy to multinational capital

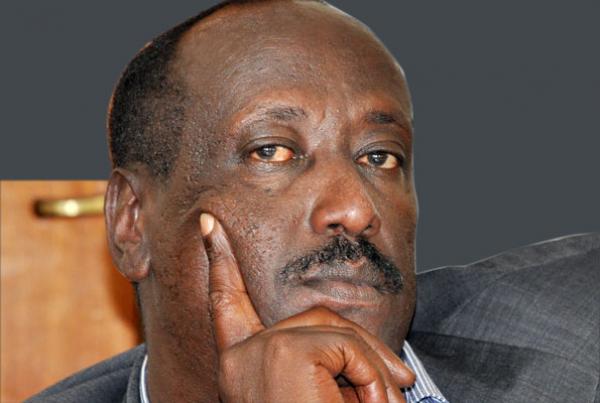

THE LAST WORD | Andrew M. Mwenda | This column last week had a discussion, with Gen Salim Saleh about the meaning of Uganda’s economic reforms of the 1990s, that generated a lot of debate on social media. Saleh also participated in some of them in spaces not accessible to everyone. Some questions dominated this discussion: did the reforms sell the commanding heights of Uganda’s economy to multinational capital? If yes, was this necessarily bad for Uganda? Did the leadership of NRM have a better alternative? If yes, was it feasible in the specific circumstances of the time? Why did neoliberal policy prescriptions gain wide acceptance, yet they were reversing gains of nationalisation and indigenization of the economy the country had realised since independence?

It is impossible to answer all these questions in one column. But briefly, people like the economist Fred Muhumuza said that many assets (like government pool houses, hotels, etc.) were sold to multitudes of Ugandans. But these did not constitute the commanding heights of the economy in major sectors like manufacturing, telecommunications, banking, insurance, etc. Others argued that the entry of multinational firms in these sectors has been a boon for Uganda. It removed state patronage, corruption, introduced better work ethics, new management styles, greater use of technology and removed government red tape.

True but at what cost?

Therefore, I am more inclined to deal with the feasibility of alternatives in the specific circumstances of the time. We must remember the NRM came to power criticising neoliberal policies. They started off with policies such as price and foreign exchange controls, barter trade, import licensing, etc. These policies, even if theoretically good, required a much more robust state. Yet in 1986, the state and economy had collapsed. There was no capacity to implement such policies even if they had had a chance of succeeding, and they didn’t. Thus, privatisation of public enterprises, liberalisation of the economy and removal of onerous state regulations was necessary to set the growth ball rolling.

Ezra Suruma, one of the key economic players of the time, once told me that by 1987 Uganda was broke. “We had only two weeks of fuel imports,” he said, and the country was facing a growing insurgency in the northern region.” He said the economy was contracting and needed foreign money to pay for basic state functions but also to buy spare parts to restart industries that had ground to a halt. Reforms in the Soviet bloc countries had closed off cash taps. The only source of money were Western countries who insisted that NRM first reach an agreement with IMF. The IMF insisted on neoliberal reforms as a condition for its money and to signal Western countries to lend Uganda money.

“We had no choice but to swallow the bitter IMF pill,” Suruma told me.

Hence, the NRM government initially adopted neoliberal reforms, not out of conviction, but out of desperation. However, as the economy recovered under the impetus of these reforms funded by Western cash, NRM consolidated itself politically. As a result, a conviction grew that these reforms actually work. Consequently, President Yoweri Museveni personally and NRM generally embraced these reforms and pursued them as their own. In the ensuing enthusiasm, all caution was thrown to the wind. Museveni and many of his NRM acolytes, people in the press (like me and Charles Onyango-Obbo etc.) became more catholic than the Pope.

It is easy today, with the benefit of hindsight, to criticise Museveni and NRM’s embrace of these reform prescriptions. But at the time, they sounded realistic and correct. Besides, they placed the economy on the long-term trajectory of growth. Thus, although the economy achieved allocative efficiency, the reforms did not provide the necessary impetus for structural transformation that lies at the heart of development.

Almost 40 years later, Uganda remains an agricultural economy.

Experience shows that an activist state actively involved both in nurturing private enterprise and willing to act as a productive agent in its own right is necessary for development.

Uganda went full blast in handing public enterprises to multinational capital because we embraced neoliberal policy prescriptions with religious fervor. The other reason is that the state in Uganda had so deeply atrophied, it was easy to make a case for it to withdraw. The third reason was that there wasn’t much of a national/domestic/local business class to make the case for privatisation with indigenisation.

The local business class was politically weak in policy-making circles to tilt the balance in its favour. Besides, NRM was a movement of intellectual elites supported by peasants with limited influence of domestic business groups. It was therefore easy for multinational capital to capture it.

Kenya, for instance, did not go into wholesale privatisation of state enterprises to multinational capital. This was because the public sector had not atrophied as had its counterpart in Uganda. So, there was still some trust in the benevolence of the state. Secondly, Kenya had a strong national/domestic/local/indigenous private sector with both political influence and institutional mechanisms to pursue its agenda. Hence privatization involved listing public enterprises on the stock exchange where Kenyans bought shares, and the state retained significant shareholding.

The state in Rwanda had atrophied more than the one in Uganda.

However, the RPF did not pursue thoroughgoing privatisation of state enterprises to multinational capital as Uganda did. This may have been because Rwanda was too small and poor to attract the attention of multinational capital. But also, the RPF had security fears that made it reluctant to sell everything to multinational capital as that would make it lose control over the economy. And finally, President Paul Kagame personally believed that Rwandans should have a stake in the economy and therefore resisted the wholesale surrender of state enterprises to multinational capital.

Tanzania too avoided the worst-case scenario of selling everything to multinational capital. I suspect this was because Julius Nyerere’s socialist ideas of state control still enjoyed a strong appeal within the ruling CCM party. Neoliberal reforms were therefore not pursued with the kind of enthusiasm we find in Uganda. Therefore, Uganda’s problem was not that it accepted privatisation and liberalisation. Rather, it carried out these reforms with very little local participation in buying those sectors that controlled the commanding heights of the economy. Locals did get a slice of public enterprises – government pool houses, small regional hotels, etc. but these were mere crumbs falling off the dinner table of multinational capital.

****

amwenda@ugindependent.co.ug

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Why can’t you go full swing and accept that those neo-liberal reforms were not in our best interest in the manner and way they were conducted? They failed and a reckoning is due, it is time for the government to reclaim some key sectors without going the “nationalization ” route. GOU should support Government alternatives in every sector, whether it’s banking, Telecommunications, Education, Health, Internet Energy, etc. They should lean heavily on the CCP model and replicate “state capitalism”.

Thank you.

Grandfather of the oldest man in the clan.