The president’s brother’s insights about Uganda’s political economy and what it tells us about our country

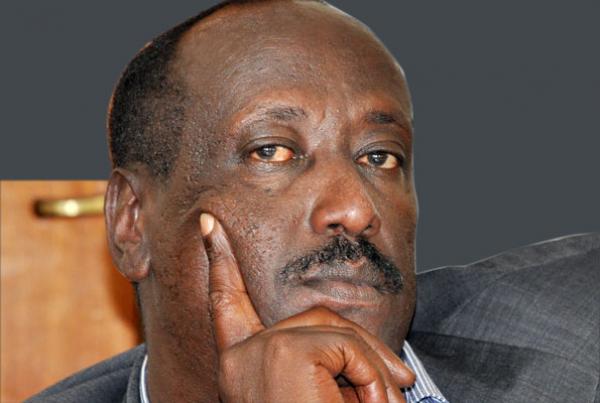

THE LAST WORD | Andrew M. Mwenda | And so, on Monday this week I visited Gen. Salim Saleh in Gulu and we sat down to a long conversation about Uganda’s economic woes. Saleh has been studying Uganda’s history for a while, focusing a lot on our political economy. Over the years, he has become a policy wonk with a vast treasure trove of historic knowledge. This has made it possible for him to place policy debates in a broad historical context and hence give critical insights to the challenges of policy making. I have had many discussions with Saleh on Uganda’s political economy, but Monday’s discussion was profound.

Saleh said that to understand Uganda’s current economic dilemma, one must begin with the advent of colonialism. That sounded like his brother, President Yoweri Museveni, who often begins a discussion of Uganda’s politics from two million years ago. Yet Saleh was different. He said colonialism sought to take control of the economy of Uganda from the indigenous peoples and place it in British hands. The agency for this process was the formation of the Uganda Company founded in 1903 with British shareholders. The Uganda Company was to be the industrial arm of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), a “civil society” agency for British rule in Uganda. I had always thought CMS was only the ideological arm of colonialism, not an industrial and business agency. Saleh told me that BK Barrop, who introduced cotton seeds in Uganda in 1903, was one of the founding shareholders in this company.

The interesting twist in Saleh’s narrative was that, the first attempt at the nationalization of Uganda’s economy began in 1953. It was initiated by Governor Andrew Cohen and was occasioned by the creation of the Uganda Development Corporation (UDC). The aim of UDC was to be the industrial arm of the state of Uganda, which would work to serve the interests of Ugandans. Cohen, Saleh said, was a socialist and was serious about promoting the participation of Ugandans in the economy through the agency of the state. British socialists were committed to this policy.

To Saleh, after independence, the government of Milton Obote sought to accelerate this nationalization process. It created institutions like the Uganda Commercial Bank (UCB) and others. In 1969, Obote deepened this process when in his Move to the Left policy pronouncements, the state took 60% stake in all foreign companies especially in banking, insurance, manufacturing, large estates etc. To Saleh, this was a struggle by Ugandans to gain control over the economy. However, he said, Obote used it to also wrestle control of the economy from Ganda capital, after his fall out with Mengo. Saleh told me that Obote used cooperatives to acquire assets of Ganda capitalists, and therefore build a political base for his political party, the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC).

“Cooperatives therefore became the economic arm of UPC to control crop marketing and in the process solidify Obote’s political support among peasants,” Saleh told me. He said that Obote systematically undermined voluntary cooperatives and strengthened state-sponsored ones. “To understand the power of UPC among the peasantry, you have to study the influence of state sponsored cooperatives,” Saleh said, “But it also means that to dismantle UPC influence in rural communities necessitated dismantling these cooperatives.” I winked at this because it provides an important insight into the thinking that led NRM to dismantle cooperatives.

The third phase in Uganda’s economic evolution, Saleh argued, was indigenization. This, he argued, was carried out by Idi Amin and was occasioned by the chasing away of Indians and other foreign capitalists beginning in 1972. Their assets were handed over to indigenous Ugandans or to the state. However, Saleh added, Obote was earlier moving in that direction but in a more sophisticated and cautious manner. Amin’s approach was not just quick and decisive but also crude. His critic of Amin was therefore not the direction of change but the speed and manner of that change.

As I was chewing over these phases, Saleh delivered to me what I felt was the most revolutionary of his arguments.

He said that the fourth phase in the struggle over Uganda’s economy was liberalization and democratization that began in the early 1990s. For him, this was the effort by multinational capital to recapture Uganda’s economy. Its aim was to dismantle both state and indigenous control of the commanding heights of the Uganda’s economy and hand it back to multinational capital. It came with a strong ideological backing, presenting itself as neutral economics – privatization, deregulation, liberalization, and the independence of the central bank.

For Saleh, the return of foreign capital to control the state and economy of Uganda, needed the weakening of the state. While privatization took assets from the state, the insidious institutional innovation, he said, was agenc-ification and projectization. He said the main state bureaucracy was emasculated through the creation of agencies and other semi-autonomous government bodies. These were funded by international “donors” and took power away from ministries. Even within ministries, most money went to donor-funded projects where staff were paid better and therefore loyal to these foreign interests. He said democratization now allowed donors to sponsor “civil society” and the press, and thereby create an intellectual vanguard to justify multinational control of our economy.

I sat in silent wonderment, listening to this lion of a man discourse on our political economy from a reclining chair. I wondered whether he appreciated the magnitude and meaning of his historic tour de force. At a personal level, it was an indictment to the many things I had defended as a young journalist – privatization, deregulation, liberalization, democratization etc. But at a political level, Saleh had delivered the most stinging criticism of his brother anyone in Uganda has done. Basically, he was arguing that Museveni sold Uganda back to foreign capital. I was stunned and asked him if he has discussed this with Museveni.

It is a question he was not interested in answering directly and insisted we focus on the historical development of Uganda’s political economy. He said all he wanted was to dissuade me from the belief that ideas are interest neutral. He said they are interest begotten. When international donors sponsor policies, it is not because of their inherent merits but because of the interests that they serve. He said what Africa has lacked are strong indigenous and national economic forces with interests to advance and intellectuals to generate justifications for them. After more than four hours, I left thinking.

****

amwenda@ugindependent.co.ug

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

But this is professor lwanga Lunyingo’s narrative with Robert Kabushenga a few weeks ago.

Read Lunyingo’s ‘ Uganda an Indian colony’. It’s apparent you are just sycophanting for Saleh, to make him look an original thinker, or you are not well informed yourself. Those are not his ideas but Prof. Lwanga Lunyingo’s research in his book that M7 disparaged recently l.

Nice advertoriol.

Anyone can talk and just talking, as Sahel, is easy but action is what matters the most. Under Musevenism and his brother Saleh, public resources and co-operations have been robbed to their family and clan to entrench family rule. Museveni’s regime will always go in Ugandan history as one of the most scandalous regime. Many of the foreign interests are his mafias. Those guys care less about Ugandans, theirs is to capture, sack it to the core, ensure their family and clan have all the economic resources and power to control the rest. When you see policies such as nationalizing one of the best performers like UMEME or UCDA, just think where we are heading. Disaster

@Andrew Mwenda, thanks for the insightful piece on Uganda’s political economy. However, take note that cotton was introduced by Kristen Eskildsen Borup, an industrial missionary in 1903 (NOT BK Barrop). It’s recorded that he distributed 62 bags of seeds then for planting. The Uganda Cotton Company, with Borup as manager, was founded in 1904.

Why did he ignore attempts at indegenizing the economy during the anti colonial struggle such as the formation of UCB and Buganda cotton riots?

What most people implicitly and explicitly take as selling Uganda at the time even upto was and is wat was needed and wat is needed to ressurect the deeply sunk and dead economy molested by its political climate wayback after independence and upto now …in life there is a time you need being bailed out of a big pitfall and at that time the discussion is about the cost but rather being brought back to your feet 🐾 cos even if it hadn’t been sold back then and now the chances of self resurrection were slim to none.this brings me to an example most of you might relate with stretched from the Bible, Lazarus (uganda )was gotten back to life by Jesus (multinationals) by the request of his sister mother and Mary (uganda government mainly the executive) but even if Jesus had made any requests to bring there brother to life im of the impression they would trade anythg for their brother ……thts the very case for uganda ,cos we were and we are still not availed with more valid options tht might bring us back to life from the deathly hallows at the speed of multinations cos surely they offer the quickest fix for the cancer that tied the knot with our economy …so as we try to ridicule multinationals we should acknowledge where they got us from and come to a conclusion that what cant be cured must be endured…we are not yet ready to stand alone or even with the try and error other than the tried tested and proven multi nations 0759867668(WhatsApp)

What most people implicitly and explicitly take as selling Uganda at the time even upto was and is wat was needed and wat is needed to ressurect the deeply sunk and dead economy molested by its political climate wayback after independence and upto now …in life there is a time you need being bailed out of a big and deep pitfall and at that time the discussion isnt about the cost but rather being brought back to your feet 🐾 cos even if it hadn’t been sold back then and now the chances of self resurrection were slim to none.this brings me to an example most of you might relate with stretched from the Bible, Lazarus (uganda )was gotten back to life by Jesus (multinationals) by the request of his sister mother and Mary (uganda government mainly the executive) but even if Jesus had made any requests to bring there brother to life im of the impression they would trade anythg for their brother ……thts the very case for uganda ,cos we were and we are still not availed with more valid options tht might bring us back to life from the deathly hallows at the speed of multinations cos surely they offer the quickest fix for the cancer that tied the knot with our economy …so as we try to ridicule multinationals we should acknowledge where they got us from and come to a conclusion that what cant be cured must be endured…we are not yet ready to stand alone or even with the try and error other than the tried tested and proven multi nations 0759867668(WhatsApp)

So surprised that Andrew M9 just discovered last week that UPC’s government was more pro-peasants who constituted the majority, hence leading to the establishment of indegeneous institutions like Uganda commercial bank, rural cooperative societies amongst others as a bond between the political leadership of the time with the citizenry. Unlike the NRM project which, instead of building on what was there, after capturing power, sought to dismantle this organic bondage between the people and political class! In other words what Gen Salim Saleh was telling you was he’s come to the realization that his brother’s mission was simply to capture power for its own sake and keep it at whatever cost, thus far, it explains why after almost four uninterrupted decades in power and probably still counting Uganda still remains a net recipient of foreign aid for her survival.

From M9’s discussion with Mr Tibuhaburwa’s young brother Gen Salim Saleh, had the “swines” remained at the political apex of this country for 20+ years, by now Uganda would probably not be too far away from countries like Malaysia, South Korea, or even Singapore!

As a way of subduing the stubborn peasants, Mr Tibuhaburwa had to device means of impoverishing them in order to rent their loyalty to him/ NRM, hence dubious projects like NAADs, operation wealth creation, now parish development model, even direct “brown envelopes” etc. to keep the citizenry in a vicious cycle of want of basic needs.

Oh Uganda May God uphlod Thee

The beginning of the cooperative movement in Uganda can be traced as far back as 1913, when the first Farmers’ Association was founded by African farmers. This was in response to the exploitative marketing systems that were against the native farmers.

Thanks for visiting the economic revolutionary leader, It’s always a lesson for us who loves and wish for our country to be transformed both politically and economically and lastly we thank God for giving us the independent magazine

Appreciated but when will the praise singing stop. In the recent past, you have been awed by HE Paul Kagame, Gen. MK and now Gen. Salim Saleh Rufu.

I have always wondered which political route Uganda takes but now, it seems clear that we may take the Cuba Route where Raul Castro the brother to Fidel Castro succeeded him in a ‘smooth’ transition.

Andrew – are you now preparing our minds for a possible Saleh Presidency when, finally, Mzee bows out possibly in 2031

Has project MK been postponed to the foreseeable future.

Granted – Saleh has already demonstrated to be a hands on leader, a fearless problem-solver… Are my fears confirmed then… You can’t just be praise singing and I believe we haven’t heard the last of Gen. SS.

IT DOESN’T CUT IT

Andrew Mwenda is at it again…. Playing 4D chess. There was nothing mesmerizing about Salim Saleh’s revelations even to the ordinary mind. The revelation that the “Uganda company” was used as an economic tool to trim and downsize Buganda’s economic interests, is largely untrue. First, before colonialism, Buganda didn’t have a viable “cash economy” to write home about…. It is in fact, the British that introduced the “cash economy” in the kingdom in the first place. Secondly, slave trade had been abolished for years…. The main reason as to why the colonialists introduced a cash economy was for the simple fact that the administrative costs had hit through the roof and as such it was becoming more difficult for the British taxpayer to continue to meet the empire’s spending. So, Salim Saleh’s revelations can’t be any further from the truth.

During Obote 1966- 71 administration, there was a loud romance with socialism….the common man’s charter. Which was about the majority rule and nationalisation of private and foreign business entities. It was vehemently opposed even within UPC. What Obote was fending off…was the humongous opposition from the wealthy individuals who aligned with the Mengo establishment. Obote used the policy of nationalisation and privatisation…to fight off political dissention and “reward” political loyalists alike…. this he did with gazetting lake Mburo as a national game park …in the case of Mzeei Boniface Byanyima…. and Coffee Marketing Board…in the case of Oyite O’jok. With the 1975, land decree, Idd Amin must have carried right from where Obote had ended…. By nationalizing land, Amin was fighting off Obote’s loyalists… it’s his methodology that had only differed from that of his predecessor. When president Museveni came in 1986, he sought for ways of both fighting off Idd Amin and Obote’s loyalists and again trying to build his own “loyal ground.” So, through privatisation and the “return” of properties for the departed Asian community, Museveni was able to shoot two birds with one stone. The return of the Asian properties also meant the “deprivation” of persons who had been “rewarded” by the Amin regime….that was the reverse side. The obverse side of the coin was the way the”return of the Asian properties” was to be structured. Remember that Idd Amin had paid off the said departed Asians, why then, was Museveni feeling so nice and generous to”double pay?” With the creation of the”Custodian Board”, which was entrusted with rent collections from the properties and overseeing the transition process….is telling. Salim Saleh through Juma Seiko was unofficially entrusted with the works of the custodian board….so, money was collected/is collected as “rent” by Juma Seiko and passed on to Salim Saleh….who “pays-off” the so called property owners and in return…he (Saleh) gains “personal ownership” of the said property. In the public eye.. the property is”returned ” to the Asians but from the”documentation”, the owners are different.

But there’s also the angle of palace politics…. from the times of the bushwar, it is said that there were two power camps….one camp for the educated and represented by the likes of Nyakayirima, Gregory Muntu, Tumukunde, Tinyefunza, Elly Tumwine…etc and the uneducated group being led by Salim Saleh, Rwigyema, Kazini etc. That Salim Saleh regards himself as the patron of this group….and along the way he managed to court his nephew Muhoozi… the rift between Muhoozi and Rwabwogo bears this element. And it won’t be far-fetched that even Andrew Mwenda is a fervent member. So, it’s not surprising that Mwenda found the time to write about this meeting.

Very interesting

I definitely agree ,Had it not been power of multinational capitalists, museven would have lost grip of Uganda yesterday.

Here for the comments…