Uganda Police Force less trusted and one of the most corrupt on the continent

COVER STORY | RONALD MUSOKE | For every two citizens across Africa, one thinks “most” or “all” police officials in their country are corrupt, according to the latest round of continent-wide surveys done by Afrobarometer, a pan-African, non-partisan survey research network that routinely does research on African experiences of democracy, governance, and quality of life.

The recent surveys done between late 2021 and mid-2023, saw researchers affiliated to Afrobarometer in 39 African countries including Uganda interview 53,444 African citizens on issues of police misconduct, criminal behaviour, brutality and corruption.

The researchers say while experiences and assessments vary widely with countries such as Burkina Faso, Morocco, and Benin scoring relatively well across multiple performance indicators, police in Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Uganda, and Kenya come off worse.

Once again, it is corruption that African citizens accuse police of practicing both openly and in subtle ways. The citizens say they are quite often confronted by police with requests for a bribe, gifts or favours. In many African countries, the respondents say being stopped for no reason may sometimes be a prelude to being asked for money by police. Similarly, asking for police assistance may prompt a demand for under-the-table payments.

Among respondents in the 39-country sample who asked for police assistance during the previous year, more than half (54%) say it was “easy” (37%) or “very easy” (17%) to get the help they needed. More than three-fourths found it easy in Burkina Faso (77%) and Mauritius (76%), though no more than half as many say the same in Malawi (37%), Madagascar (37%), and Sudan (33%).

Namibians and Batswana were most likely to ask for police assistance (29% each), while Tunisians, Ivorians, and Malagasy (7% each) were least likely to do so. Contact with the police in other situations was highest in Cameroon (65%), Liberia (63%), and Nigeria (62%) and lowest in Madagascar and Senegal (12% each).

Among 13% of respondents who said they had asked for police assistance during the previous year, 36% of them said they were asked to pay a bribe, give a gift, or do a favour to get the assistance they needed from the police. The Liberian police is most notorious when it comes to practising this vice (78%), followed by the police of Nigeria (75%), Sierra Leone (72%) and Uganda (71%). The practice is least common in Seychelles (4%), Mauritius (3%), and Cabo Verde (2%).

According to the findings, although citizens are more likely to encounter the police in situations other than actively asking for assistance, the rate at which they are asked to engage in corruption is often very similar irrespective of the reason for the contact with the police.

For example, in Liberia, 70% of respondents say they had to pay a bribe to avoid a problem with the police. On the other end of the spectrum, very few were asked to pay a bribe when encountering the police in the Seychelles (2%) and Cabo Verde (1%).

Police presence and contact

As part of the data collection process, Afrobarometer field teams made on-the-ground observations to identify facilities and services that are available in each census enumeration area (EA) they visit or “within easy walking distance.”

Across 39 countries, fieldworkers found a police station in 36% of surveyed EAs and reported seeing police personnel or vehicles in 31% of them. Signs of other security-related activity were less common, including soldiers or army vehicles (12%), police or military roadblocks (10%), private or community checkpoints (6%), and customs checkpoints (4%).

On average across 39 countries, Afrobarometer teams found police presence – either a police station or police personnel/vehicles – in 46% of surveyed locations. The police presence was far more common in urban than in rural areas (64% vs. 29% on average).

This pattern held true in all surveyed countries except in Mauritania (67% urban vs. 76% rural), Mauritius (64% vs. 81%), and Cameroon (71% vs. 72%) – the three countries with by far the highest rural police presence. Urban police presence was highest in Morocco (94%) and Tunisia (85%). It was lowest in Zambia (29%) – still far above the lowest rural police presence (6% in São Tomé and Príncipe and none at all in Seychelles).

Similarly, police presence tended to be much higher in EAs with better road infrastructure: 66% in areas with paved, tarred, or concrete roads, compared to 36% in EAs with earth, gravel, stone, or murram roads.

“A higher density of police stations and more contact between police officers and citizens might be good, as it might mean better access to police assistance and better collaboration,” the researchers say.

Professionalism in Police

Beyond their personal experiences when seeking assistance, most African citizens have a sense of how professional they think their police force is. The respondents were also interviewed about the professionalism of police in their countries. The respondents were asked: In your opinion, how often do the police in (your country) operate in a professional manner and respect the rights of all citizens? (% who say “often” or “always”).

On average across 39 countries, only about one-third (32%) of respondents say the police in their countries “often” or “always” operate in a professional manner and respect the rights of all citizens, while 32% say they “sometimes” and 34% say they “rarely” or “never” do. In just six countries do at least half of citizens think their police usually act professionally: Burkina Faso (58%), Morocco (57%), Niger (55%), Benin (54%), Mali (54%), and Senegal (50%).

According to the findings, older people (37% among those aged 56 and above) and rural residents (36%) are more likely to see the police as “often” or “always” meeting this standard than youth (29%) and urbanites (28%). On the other side, younger people, men, and poor citizens are also particularly likely to have to pay a bribe when they encounter the police in such situations.

In fact, 44% of the poorest respondents who had contact with the police during the previous year say they had to pay a bribe to avoid a problem, almost twice as many as in the well-off group (24%). While rural residents are less likely than urbanites to encounter the police, they are more likely to have to pay a bribe when they do (40% vs. 34%).

‘Police more corrupt than tax officials’

Considering how many Africans personally experience having to bribe the police, it may not be surprising that on average across 39 countries, the police are more widely seen as corrupt than other public institutions or leaders the surveys ask about.

Respondents were asked: How many of the following people do you think are involved in corruption, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? Almost half (46%) of respondents said that “most” or “all” police officials are corrupt, compared to almost four in 10 who see widespread corruption among Members of Parliament (legislators), tax officials, civil servants, officials in the Presidency, business executives, and judges and magistrates. In contrast, roughly one in five citizens perceive “most” or “all” traditional (22%) and religious leaders (19%) as corrupt.

According to Afrobarometer, the “most corrupt” ranking for the police is not a new development; previous rounds of Afrobarometer surveys have shown similar patterns. However, when country specific data is dis-aggregated, the police are not perceived as the most corrupt actor in every country.

While the perception is true in 19 of the 39 countries –and by wide margins in Uganda and Zambia – in the remaining 20 countries, at least one of the other institutions or leader groups is more widely seen as corrupt than the police.

Criminal activities by the police

According to Afrobarometer report, worse than asking to be paid extra to do their jobs, some police officers actually do the opposite of their jobs: Three in 10 Africans (29%) say the police in their country “often” or “always” engage in criminal activities. Another 27% of respondents say they “sometimes” do so, while only 36% say the police “rarely” or “never” commit crimes.

The perception of widespread criminality (often/always) among the police is shared by more than half of citizens in Lesotho (58%) and Senegal (51%). At the other extreme, majorities in six countries say criminal activity by the police is rare or unheard of: Benin (71%), Ethiopia (63%), Tanzania (61%), Morocco (61%), Mauritania (57%), and Burkina Faso (52%).

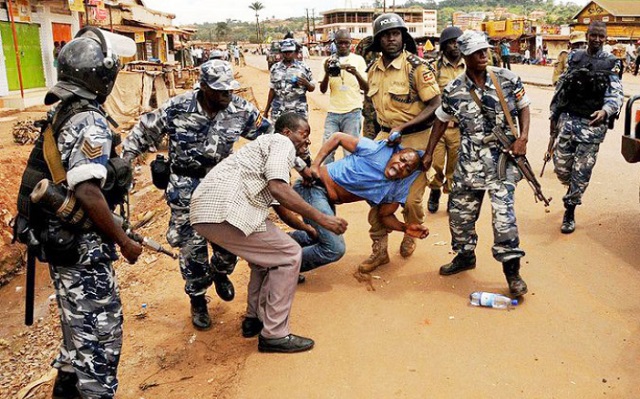

Police brutality

One of the harshest criticisms levelled against some police officers is that they use excessive force in their interactions with the citizenry they are meant to serve and protect, whether against protesters, political dissidents, or people suspected of crimes.

The respondents were asked: In your opinion, how often do the police in (your country) use excessive force in managing protests or demonstrations? According to the surveys, almost four in 10 respondents (38%) say the police “often” or “always” use excessive force in managing protests or demonstrations, while another 27% say they “sometimes” do so. Only 29% say the police are “rarely” or “never” guilty of brutality in their handling of protesters.

The perception of widespread police brutality in dealing with protesters is most common in Gabon (64%), Senegal (60%), Kenya (57%), and Uganda (57%), and least common in Mauritius (17%), Cabo Verde (17%), and Seychelles (12%).

A similar picture emerges with regard to how the police deal with criminal suspects: On average, 42% of Africans say the police “often” or “always” use excessive force, and another 28% say they “sometimes” do so. Only one in four respondents (25%) think the police “rarely” or “never” treat suspected criminals brutally.

The perception of frequent police brutality in dealing with suspected criminals is most common in Senegal (62%), Gabon (57%), Tunisia (56%), and Lesotho (56%), while about one in five citizens say the same in Mauritius (21%), Madagascar (19%), and Seychelles (18%).

According to the survey, there are also divergent experiences with and perceptions of police. For instance, the survey found that urban residents (45%), younger people (40%-45%), men (46%), and poor citizens (43%) are more likely to encounter the police at checkpoints, during identity checks or traffic stops, or during an investigation than rural residents, older people, women, and well-off citizens.

Police brutality in Uganda

In August, 2023, Afrobarometer’s Ronald Makanga Kakumba and Matthias Kroenke, noted in a policy brief titled, “Brutality and corruption undermine trust in Uganda’s police: Can damage be undone?” how over the past two decades, the Uganda Police has lost a lot of its most important currency – public trust.

The Uganda police is responsible for enforcing the law, preventing crime, maintaining public order and security and protecting people’s lives and property but, it has quite often been criticized for brutality meted out against the very citizens meant to be under their protection.

A majority of Ugandans say that most of all members of the police are corrupt and that they frequently use excessive force in dealing with suspected criminal and managing protests.

Makanga and Kroenke said without this public trust, it is more difficult for the police to get public support for crime prevention measures, community safety initiatives and criminal investigations.

Police presence and performance

According to the findings, police presence and contact are not significantly correlated with perceptions of police professionalism, police corrupt behaviour or police brutality but, the researchers say high levels of police professionalism are correlated with perceptions of less police corruption and police brutality.

According to the surveys, perceived police professionalism is strongly associated with citizens trust in the police. “Countries with higher scores on police professionalism tend to record better government performance evaluations on crime,” notes the report in part.

On average, across 39 countries, 48% of the respondents say they never felt unsafe walking in their neighbourhood during the previous year, and 59% say they never feared crime in their home. Lower perceptions of corrupt activity by the police are significantly associated with more widespread feelings of being safe in one’s surroundings.

Fewer than four in 10 citizens (37%) say their government is doing “fairly well” or “very well” at reducing crime, ranging from just 10% in Sudan to 77% in Benin. Fewer than half (46%) of citizens say they trust the police “somewhat” or “a lot.”

In his recent paper, “The Causes of Police Corruption and Working towards Prevention in Conflict-stricken states,” Danny Singh from the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Teesside University, U.K, says, the police are the initial faces of law enforcement and often initiate the criminal justice process and thus hold significant responsibility for functioning law and order.

He says negative public perceptions of the police are particularly troublesome in violently divided societies or states undergoing armed conflict since “Poor credibility of the police could also have a negative impact on the legitimacy of the government.”

Dr. Solomon Asiimwe, a lecturer of governance at Uganda Martyrs University, Nkozi, told The Independent on March 16 that he is not surprised by the latest findings of the Afrobarometer surveys. Dr. Asiimwe who has written several papers on the police institution in Uganda and the African continent gave several reasons why the police are perceived by African citizens as “the most corrupt.” “It all starts with the nature of the African state; it is still yet to emerge from its colonial legacy,” he said.

“Most African countries continued with the colonial structures and mentality they formed around institutions like the police,” he told The Independent. “The African police was built mainly as a law enforcement agency and it was structured in a way of being anti-people.”

Dr Asiimwe further went ahead and contextualized the reason as to why the police are perceived as “most corrupt and brutal” by most African citizens. He told The Independent that the police interface more with people in the communities compared to, for instance, the military. “If the army had the same level of regular engagement with civilians, they too would be perceived the same way,” he said.

But he also argues that there has been a general breakdown of the civil service in most of the African states. Dr. Asiimwe says the recruitment of police personnel is not only suspect but their training is often not good enough. “When it comes to recruitment, do we get the best?”

He says the police often recruit people with fewer options in life and they only join the police to survive and not serve the people. “And when they eventually join the police, they face so many challenges; ranging from poor training but also poor remuneration.”

“In the United Arab Emirates, you cannot easily corrupt a police officer because they are well paid and in Rwanda, the police officer is not corruptible because of the enforcement mechanisms that are in place.”

Dr. Asiimwe says a combination of poor standards and lack of values to guide most of the police institutions on the continent explains their performance and relations with citizens.

How Africa’s Police Services compare

Afrobarometer scored each of the police in the surveyed countries by creating four indices that combine respondents’ personal experiences with broader perceptions of the police by averaging several questions for each dimension (professionalism, corruption, brutality and presence/contact).

Burkina Faso (68%), Morocco (64%), and Benin (61%) scored highest on the professionalism dimension while achieving moderate (Burkina Faso and Morocco) to high (Benin) scores on the corruption measure (moderate to low levels of corruption).

In contrast, Sudan (30%), Sierra Leone (30%), Gabon (29%), and Congo-Brazzaville (28%) scored worst on professionalism while also showing moderate to poor scores in terms of corruption and police brutality.

“The 39-country averages re-emphasize our finding that police performance remains inadequate in most countries,” the researchers said.

They also note that when people view the police as untrustworthy, they are less inclined to comply with the law, might even resort to taking the law into their own hands, and are less likely to cooperate with the police in ways that would enhance the effectiveness of law enforcement.

“Our findings point to broad cross-country patterns of how police professionalism, integrity, and respectful conduct are correlated with more positive citizen attitudes toward the police.”

Going forward, Afrobarometer says, African governments looking to confront the challenges of improving unfavourable public perceptions of the police – and of government performance in the fight against crime –might take a closer look at which dimensions of police performance matter in their country, and which better-performing police forces might have solutions to share.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price