Threats that journalists will be criminally liable if they don’t register can’t cover up outdated policies and bad intentions

Kampala, Uganda | JOSEPH WERE | It is great news that journalists have once again ignored the recent directive by the Minister of ICT and National Guidance, Chris Baryomunsi, to register and buy licenses from the Uganda Media Council.

That does not mean journalists do not see that Baryomunsi’s fight against fake news, misinformation, cyber-bullying, and pornography is noble. They do. But they also see that his push for journalists to be registered by the Media Council is ignoble.

Baryomunsi is not the first minister of Information to attempt to license journalists. They all fail for three very simple reasons; they fail to recognise that the Uganda Press and Journalist Act (1995) they base on is archaic, do not recognise that journalism has evolved and requires new forms of regulation, and, most importantly, journalists see their move as government aiming to control them when what is required is facilitation of journalists.

The Uganda Press and Journalist Act (1995) is outdated. The policy that Baryomunisi is peddling was developed in the 1990s when the main feature of journalism was static media, basically the printed newspaper by established media houses such as the New Vision and The Monitor. Electronic media, such as TV and radio were limited to government-owned outlets and two or three FM stations. These media operations were analog; meaning that what was carried reflected its original source and was difficult to alter. That implies that the purveyor was easy to hold to account.

The law focused on two media roles only; the “editor” defined as a person who is, at any given time, in charge of programme production at a radio or television station and the “journalist” who is a person enrolled with the prescribed journalists organisation. Editors of print media were regularly sued, jailed, and even killed. Later, with proliferation of privatisation, owners of printeries joined the hordes of the harassed. But that is in the past.

Today, the definition of journalist is also evolving. Baryomunsi is focused on the traditional journalist who is attached to a known media house and has a job description such as reporter, editor, news manager, or programmed director. Yet anyone can make and publish a video and be a journalist. News is interactive. The audience contributes to the content. We have bloggers, influencers, twitterati, and netizens who generate or actively engage with the news via comment, re-tweets, liking, and more. Online media have new influential specialisations such as software developers, web and app designers, interface designers, illustrators, motion graphic designers, and more. Many producers of digital news content are not journalists, are not based in Uganda, and are below the mandatory age of 18 years, and do not operate under any established media house. Today we have citizen journalists, civic journalists, activist journalists, and more. The old journalism centre cannot hold.

Even established media houses are now multimedia platforms. They are in print, in electronic form such as radio and TV, and digital such as websites, blogs, spaces, tweets, and other social media. Baryomunsi should know that chasing and catching the purveyors of news on these many platforms is impossible. They are defined by speed. Their news sites open and close at fast pace. Some of the information generators are faceless, such as Tom Voltaire Okwalinga aka TVO, while other news is generated by automated software or BOTs, anonymous undercover investigators such as Anas Aremeyaw Anas of Ghana, or by global collaborations such as the Pandora Papers.

Baryomunsi will fail because he, like his predecessors, is pursuing control of journalists when what is required is facilitation of journalists.

The Uganda Press and Journalist Act (1995) was enacted “to ensure the freedom of the press, to provide for a council responsible for the regulation of mass media and to establish an institute of journalists of Uganda. And it provided for formation of a National Institute of Journalists of Uganda (NIJU) which would facilitate this engagement among journalists.

But Baryomunsi does not want NIJU despite the huge and unwarranted government oversight the law imposes on journalists. Baryomunsi fears NIJU because it is envisaged to be organised and run by journalists. It is designed to facilitate not control journalists and Baryomunsi wants control. That is why he prefers the media council.

The media Council does not represent journalists. It is a 13 member body comprising five appointees by the Minister of information, four nominees by media owners, three journalists, and Uganda Law Society nominee. Contrast that with the Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council, for example, which has nine members; eight of whom are medical doctors and the other a legal assistant. Also note that the journalists must be enrolled with the National Institute of Journalists of Uganda (NIJU) which is prescribed by law but is not in place. The absence of NIJU nominated members means that the Media Council, its undemocratic character aside, is not fully constituted as prescribed under the law.

Baryomunsi should instead look at better informed interventions being proposed by his counterparts in other jurisdictions. At the heart of the proposed new regulatory frameworks are ideas redefining the duty of care or responsibility of media platform owners in the digital era. These are, in some aspects comparable to those of the analog era. In both cases, the owners of media platforms have a duty of care or responsibility for the public space they have created, for its employees, and its users.

Emphasis is not on censorship, fines, or jail terms but on freedom of the press. Equally significantly, the proposal recognise the role various regulators play. These include the competition and markets regulatory body, advertising standards authorities, the Information and communication regulator, financial conduct authorities, and ministries of Information and communication. Some of these regulatory bodies do not have equivalents in Uganda. Instead of pursuing journalists, Baryomunsi would make a greater contribution to setting up a regulatory framework for new era media by mobilising their formation, revamping, and coordination.

****

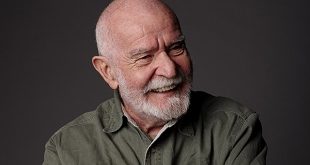

Joseph Were is managing editor of The Independent

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price