And the government fails to get the desired ‘demographic dividend’

Uganda has a bad population structure, according to population and development experts. They say Uganda’s population structure has a broad base; meaning it comprises mainly children and young non-working people aged below 14 years, making it the country with the second youngest population in the world.

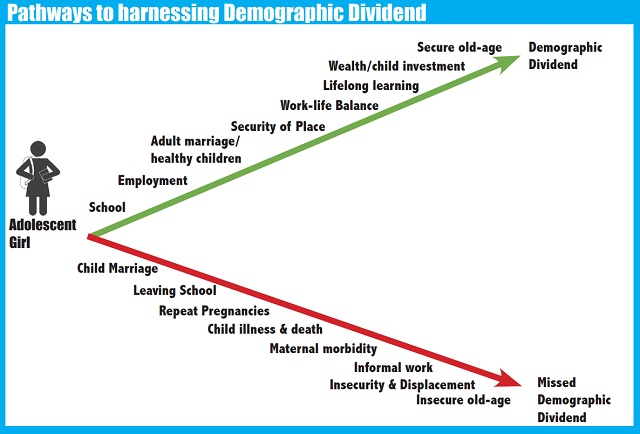

The government wants to turn around this undesirable structure so that working age people of 15 to 65 years become the majority. The objective is to hopefully achieve what is referred to as the “demographic dividend”—the economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population’s age structure.

The plan involves getting women and girls to overcome economic, social, cultural, political and geographical barriers and make informed decisions about the kind of family they want. It is a strategy contained in the policy briefs of organisations like the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) that urge governments and support agencies to plan and invest in voluntary family planning services. In other words, they say, family planning is the bedrock upon which governments must build to achieve the demographic dividend. Ronald Musoke reports on how the plan is progressing.

Fatiah Kirabira, 22, ended her formal education in S.4 and now lives in Kamwokya, a low income suburb in central Kampala.

In another part of the city is Grace Ngororano, 20, a first year undergraduate student at Makerere University. The gulf between them appears big. Yet they both agree on one thing: the desire to have few children in future.

Both say they are not sexually active at the moment but they intend to get onto one of the most comfortable modern family planning regimen once they get partners. Kirabira who was born in a family of four told The Independent that two children would be enough for her. She said she wants to give them “enough love and care.”

“I personally want to have one or two children because it is tiresome work pushing out and looking after children,” says Ngororano, “I know that I will use family planning because it is good.”

Listening to how the two young women’s dreams rhyme with the government’s grand 2040 Vision which talks about working towards a high quality population in the next couple of decades would make many sexual reproductive rights experts proud.

Population and development experts say any country with designs of reaping economic benefits of a big working population needs to deliberately increase investment into family planning services. This, they say, normally leads to fertility decline by enabling couples to have only children they want to have.

Fertility decline in the modern era is attributed to voluntary family planning, with women’s education and employment, economic protection and child survival also contributing.

“Reducing fertility also ensures that benefits don’t go to households only but these translate onto the macro-economic level,” says Dr. Jotham Musinguzi, the Director General of the National Population Council-Uganda.

Ngororano says unlike in the days of her parents, where they were fairly comfortable producing and raising many children, today’s economy cannot allow people to have many children.

“I would like to have fewer children and look after them the way my parents looked after us. They had four of us but they were very comfortable,” she says.

Judith Mutabazi, the senior planner (population, gender and social development) at the National Planning Authority (NPA), says as long as the average number of children per woman (total fertility rate) and population growth remain high and children and adolescents greatly outnumber working-age adults, families and the government will not have the resources needed to invest adequately in each child.

In her paper, “Family Planning—A pathway to harnessing the Demographic Dividend and Attaining Universal Health Coverage,” she notes that the transition to smaller families both accompanies and contributes to improved child survival.

She notes in her paper published in 2019 by the Makerere University School of Public Health that large numbers of young people can represent great economic potential, but only if families and governments can adequately invest in their health and education and stimulate new economic opportunities for them.

She says in order to achieve a demographic transition; countries must focus on providing women with voluntary family planning information and services. For example, for each 16 percentage point increase in contraceptive use, fertility rates fall by one child per woman.

In Rwanda, for example, modern contraception use which has increased fourfold over the past decade has seen total fertility rate fall to 4.6 children per woman. If the impressive progress continues, Rwanda could achieve the demographic conditions necessary for accelerated economic growth in the next eight years.

This rapid progress in Rwanda has been in part, as a result of the government’s role in supporting family planning practices which have been promoted through a number of key policies. One such policy has been the strengthening of public sector service provision (government health centres, hospitals and other public entities) which now serve almost 90% of all family planning users.

The Rwandan government has also taken steps to promote public-private partnerships (PPP) to support contraceptive commodity security. The same could happen in countries like Uganda where high fertility rates persist.

But will it happen?

Annah Kukundakwe, the Senior Programme Officer, at the Centre for Health, Human Rights and Development (CEHURD), a Kampala based sexual reproductive health rights non-profit told The Independent on April 6 that while the government and other stakeholders have done quite well in trying to increase the uptake of family planning services around Uganda, there is still unmet need for these services.

Joan Kilande, a programme officer at HEPS-Uganda, another health rights non-profit also told The Independent that modern contraceptive prevalence rate among Ugandan women stands at just 30.4 % according to 2020 government statistics.

At this pace, Kilande said, Uganda will not be in position to reach the FP2030 commitments among which include reaching 50% of Ugandan women with modern family planning services.

Uganda currently has a total fertility rate estimated at 5.4 children per woman, giving it one of the fastest-growing populations globally.

This rapid population growth has resulted in one of the youngest populations in the world, with more than half the population being younger than age 15 and more than three quarters being under age 30, while adolescents comprise up to 30% of the national population.

The high fertility in Uganda is attributed to a number of factors among them; a pro-natalist culture (preference of many children), low median age at first marriage (18.7 years) and first child bearing (19.2 years); and low uptake of contraceptives. According to the 2016 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS), more than half of the Ugandan girls have had their sex debut by age 18.

The country’s high fertility rate has also been attributed to the high unmet need for family planning, estimated at 28%; low contraceptive use of 39%; high desired family size of 5.7 for men and 4.8 for women as well as a high teenage pregnancy rate of 25%.

This desire for big families keeps the fertility rates high and poses a challenge to demographic transition in the long run and subsequently to attaining the demographic dividend. Although Uganda has registered improved economic growth rates averaging 3% per year, progress is undermined by its high fertility rate.

At the same time, although many women in Uganda want to delay or stop child bearing, many do not have access to modern contraception. The total demand for family planning services was estimated at 67% in 2016, implying existence of an unmet need for family planning of 28%.

“In Uganda, the number of women who want to delay or avoid pregnancy but are not using family planning (unmet need) is still very high,” says Stella Kigozi, a population expert at the National Population Council-Uganda.

Kigozi says while the government of Uganda has made important commitments to family planning and increased the budget for communities at the district level, investment in family planning is low. Many districts have no budget for family planning at all.

In 2016, the contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) was recorded at 39% among currently married women aged 15-49 years, with 35% of currently married women using modern methods of contraception.

Although low, these figures represent a big improvement from the 18% recorded in 2001. Among the sexually active unmarried women, 51% were using a contraceptive method, with 47% using a modern method.

Fertility levels are also lower in urban than rural areas, among women with post-secondary education and those in higher wealth segments. As more women attain higher education and engage in employment, the fertility is expected to decline at a much faster rate.

Kilande told The Independent that much as young women like Kirabira and Ngororano would like to access family planning services, the environment is not conducive for them.

Even when health facilities are encouraged to establish youth spaces; reserving hours per day attending to health needs of the adolescents or securing a day or a space for these services, these spaces have become inactive in most public health facilities, she said.

There is also the challenge of increased fear for modern family planning side effects. Kilande says teenage girls and young women have over time reported the fear for side effects, mainly due to lack of access to correct information in this target group.

But there is also the lack of clarity on messaging by the government. Kilande says most public health facilities are encouraged to preach abstinence and yet young girls in Uganda are sexually active.

Kokundakwe also told The Independent that Uganda’s legal and policy environment is not enabling for teenagers to access contraception services. The age of consent for marriage is similar to the one for consent for sex, she says.

“The presumption that our policy makers have is that young people below 18 are not having sex and therefore cannot have access to family planning services but this is of course incorrect,” she says, “We have been faced with circumstances where 15 year old teenagers are actually giving birth.”

“We have seen teenage pregnancy rates nearly double because we keep imposing upon young people things like abstinence even when their circumstances are not enabling to steer clear of pregnancies,” Kokundakwe told The Independent.

In November, last year, Dr. Jane Ruth Aceng, the Minister of Health launched the Uganda FP2030 in Kampala, an ambitious programme which government says will see access to voluntary family planning services rise by 50% by 2030.

But Kukundakwe told The Independent that beyond rhetoric, if the government wants to achieve its lofty ambitions of Vision 2040, where Uganda is an upper middle income country with high quality employed citizens, providing family planning services will be necessary.

“Without such deliberate policies, it is going to be very difficult to achieve the demographic dividend the government wishes if people are still having many children and they are not able to educate them,” she told The Independent.

Prof. Frederick Makumbi, the Deputy Dean at the School of Public Health, Makerere University,recently told a group of journalists undergoing training on Uganda’s population trends and the government’s quest to achieve the demographic dividend that “the price of inaction for the government is simply too big; as educated, unskilled, unemployed and deprived youth can also become agents of social unrest, crime and violent extremism.”

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price