Support local governments more

The AgPER report however warns that Uganda’s national decentralization objectives are not fully matched by the allocation of resources, as local governments receive a much lower share of final Public expenditure in support of the agriculture sector than agriculture related ministries.

“The allocations to local governments declined from 37 percent in 2013/14 to about 7 percent in 2017/18, falling slightly short of the Agriculture Sector Strategic Plan (ASSP) target of 10 percent. Given that local governments provide frontline agricultural services such as extension and advisory services, market information services, and rural infrastructure, their budget allocations need to be increased.”

Role of OWC questioned

“The analysis of the Public expenditure in support of the agriculture sector data across 2015/16–2017/18 reveals that Operation Wealth Creation (OWC) activities contribute to both allocative (economic and functional) and technical inefficiencies,” the AgPER report states.

Like NAADS, the OWC, one of Uganda’s biggest civil-military operations, faces myriad challenges in serving farmers, including the low number and weakness of farmer groups and institutions, late delivery of inputs, inputs of low quality and quantity, and high mortality rates in planting materials

and breeding stock owing to drought and poor management.

“The parliamentary report on implementation of OWC (Republic of Uganda 2017) argues that the introduction of OWC had several negative effects on the provision of inputs and extension services across the country, including a sharp decline in the number of extension agents at NAADS, the poor quality of inputs delivered by OWC, and the failure to deliver inputs on time or unreliability of private input suppliers.”

The report warns that much of the NAADS budget serves to buy inputs for free distribution to farmers which should not be the case. “Making inputs accessible was integral to raising agricultural productivity, but the approach used for distributing inputs is unlikely to achieve this objective, since it is not fiscally sustainable. Input procurement and distribution should not distort the market for inputs and crowd out the private sector.”

The report states that technical inefficiencies pervade the delivery of subsidized inputs to farmers. “Considerable volumes of inputs have been procured by the NAADS and distributed by the OWC, ranging from seed (maize, beans, soybeans, rice, sorghum, groundnuts, and Irish potatoes) to banana plantlets, heifers, layers and broilers, and tilapia and catfish fingerlings.”

The report notes that these inputs are not costed in the National Budget Framework Paper, but they have averaged US$100 million equivalent per year.

“The unit costs of some inputs procured were 20–50 percent higher than comparable market prices.

The inputs often were of poor quality, distributed late without communication or consultation with

districts, without extension services, and rarely with complementary inputs such as fertilizers and

pesticides. Results were not monitored. Wastage was unavoidable. Giving free inputs to farmers is

not sustainable and in the long run breeds dependency or entitlement. The government should

address these inherent technical inefficiencies.”

Role of the Agriculture Ministry

The report concludes generally that, “Public expenditures on agriculture underperform because of structural deficiencies and capacity constraints— but even so, the Ministry of Agrictulure has ample scope to improve the technical and economic allocation of public resources to spur growth in the sector.”

To achieve this improvement, the report says, MAAIF must continue with radical institutional reforms to reflect its new roles, including its role in delivering extension services (transferred from NAADS),

and reinforce its role in policy and planning.

The report says local governments should get a bigger share of PEAS than the current average of less than 10 percent. “District fragmentation, underfunding, and low capacity at the local government level have caused the quality of services to fall across the board, even though the total number of people with ostensible access to some services may have grown.”

Finally, the report recommends that “For agriculture to act as a key economic driver of Uganda’s Vision 2040 and the transition to middle-income status, private sector investment must be leveraged.”

Sugar Production

The report hails the private sector’s role in Sugar Production, giving Kakira Sugar Works as an example.

Uganda is the largest producer of granular sugar in the EAC. According to the Uganda Sugar Manufacturers Association, sugar production increased by 17 percent from about 365,452 tons in 2017 to 428,000 tons in 2018.

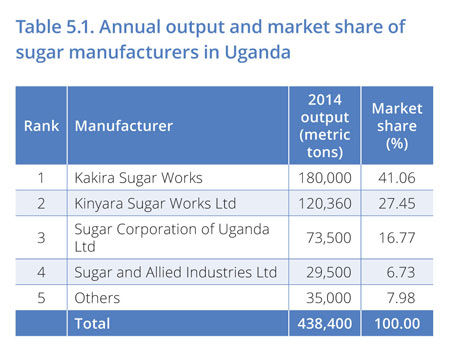

Sugar production in Uganda was for many years dominated by three big manufacturers: Kakira Sugar Works (KSW), Kinyara Sugar Works Limited, and Sugar Corporation of Uganda Limited, accounting for about 82.3 percent of the national output in 2014 (Table 5.1). In November 2011, the government licensed several new sugar manufacturers to reduce the deficits in domestic sugar production.

The KSW is a subsidiary of the Madhvani Group of Companies, the largest conglomerate in Uganda. Madhvani Group’s current turnover in Uganda exceeds US$150 million per year, and its assets are valued at more than US$300 million. The group also has investments in other EAC countries—Rwanda, South Sudan, and Tanzania.

During the 1970s, the Madhvani family was expelled from Uganda. Their businesses were nationalized and mismanaged to near-extinction. In 1986, the family returned to Uganda, revived and rehabilitated their businesses, and started new ones.

Its annual sugar output increased from 90,000 metric tons in 2006 to 152,600 metric tons in 2010 and more than 180,000 metric tons in 2014. KSW crushes over 6,000 metric tons of cane per day and operates continuously for 10.5 months per year. The company grows sugarcane on a nucleus estate of about 10,000 hectares and supplements that production with cane sourced from 26,000 hectares owned by outgrowers.

In the 2014 period the number of contracted outgrowers rose from 3,000 to over 7,500, who supply over 1 million metric tons of sugarcane, which is about 65 percent of the factory’s annual requirement.

Outgrowers normally own over 1 hectare and are located within a 25-kilometer radius of the factory.

KSW also contributes immensely to the Ugandan economy in terms of job creation, tax revenue, and environmental sustainability. The company directly employs over 8,000 persons on the sugarcane estate and in the factory.

Over 100,000 people depend on the company, and the community has seen not only jobs, but schools, hospitals, roads, and electricity arrive on the back of the sugar industry.

The company generates about 22 megawatts of power from the bagasse, of which 12 megawatts is supplied to Uganda’s national grid. The company also produces biofuels (ethanol) from molasses, which is used for blending petroleum products to reduce the dependence on fossil fuels.

THE FULL REPORT

Uganda Agriculture Sector Public Expenditure Review by The Independent Magazine on Scribd

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price