Students cannot pass without being taught, experts tell the government as 2018 UCE results show high failure rates

Kampala, Uganda | FLAVIA NASSAKA AND JULIUS BUSINGE | While releasing the results of the 2018 Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) examinations on Jan.31, the Chairperson of the Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB), Mary Nakandha Okwakol pointed at two trends; first that more students are failing science subjects. And two, that there is little science teaching going on in schools.

Okwakol said the 2018 results show that chemistry remains the worst done subject overall. She noted improvements at distinction level for subjects like mathematics, physics and biology, but almost half of the students did not achieve the minimum Pass 8 level.

“That should tickle teachers and government to think about what is not being done right,” she said, “These results are an indicator that there is little science teaching.”

At the same function, the Executive Secretary of UNEB, Daniel Odongo, pointed at another problem related to the examination of science subjects. Odongo said the highest cases of examination malpractices were registered in physics, chemistry, biology and mathematics.

A total of 335,435 students sat for the 2018 examinations, up from 326, 212 in 2017. Of these 27,696 passed in division one compared to 31, 338 in 2017, 52,706 in division two compared to 53, 665 in 2017 and 70,347 in third division compared to70, 797 in 2017. Those that passed in fourth division were 137,058 compared to 131, 660 a year before.

Odongo said impersonation and substitution were the common cases of examination malpractices which led to results of 1,825 students being withheld. He said the affected students were given external assistance while some candidates colluded to cheat.

Commenting on these developments, Robert Mugambwa, an education researcher working with Uwezo says students fail science subjects because they are taught badly.

He explained that passing sciences requires a learner to understand theories and laws, yet most schools in Uganda use the cramming method; a form of rote learning that merely prepares students to quickly pass exams.

“Cramming does not help in the sciences and yet it seems to be what is happening,” he told The Independent soon after the results were released.

He says that it is not that Ugandan students cannot to grasp science theories and laws; the problem is with the teaching system, it does not guide students enough to be able to learn the subject content, bring out their potential, and pass exams.

“You cannot forge a scientist, he has to be made,” he says.

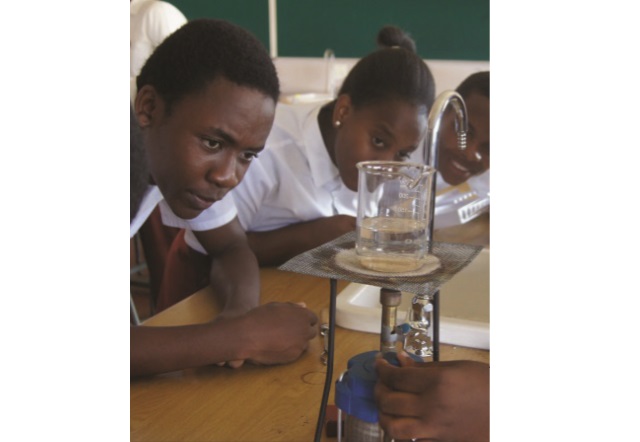

According to Okwakol, many schools; especially in rural areas, are attempting to teach sciences without having the necessary apparatus and chemicals to conduct practical lessons.

Herbert Asiimwe Mutamba, a retired sciences teacher turned author told The Independent that the government is at a loss when half of the students fail to score even a pass eight in the subjects.

“With such a mark, they can’t pursue a sciences combination at advanced level,” Asiimwe said.

Mutamba blames the government policy of making sciences compulsory for all students in lower secondary school. He says the intention of the policy was good, but the worsening performance of science subjects shows that the government should have found another way of achieving the agenda of grooming more scientists. He says imposing the subjects even on those that do not have the ability to pass them was wrong. He says, in any case, most students still go on to study arts fields at A-Level.

“That is why you see we still almost record the same percentages of students offering arts subjects at A – level, 15 years after government came up with the policy,” he says.

He adds that the government should pick lessons from this continuous bad performance.

“One would say those that fail sciences are not smart but why then do they score distinctions in the arts. They fail because they know it is not the career path of their choice,” he says.

He adds that imposing these subjects on students is only straining government resources and the difference the policy is creating on the type of science professionals on the labour market is very minimal if any.

But Grace Baguma, the executive director of the National Curriculum Development Center (NCDC) says the policy of making sciences compulsory is not the problem but the challenge is with the way it is taught.

She says when, in 2004, the government moved to ensure that all students that go through the Uganda education system must have basic knowledge in science, it was because no country has taken off economically without the involvement of scientists.

“With the change of curriculum they thought they would fix a few things and ensure that we get more numbers of scientists graduating,” she says.

She says Uganda has already trained many good scientists who are competing favourably on the international stage.

Baguma says there have been reports of scrapping or changing the policy before but she says the government should instead be looking into ways of improving the method of teaching science subjects, get more science teachers trained on the job, and ensure that schools have the necessary facilities to understand the subjects.

“We are talking of driving the country to middle income but we do not want to train those engineers and technologists to drive that economic development. Without more scientists we will remain the way we are or become worse”.

Mutamba also commented on the Secondary Science and Mathematics Teachers (SESMAT) programme that the government introduced to give science teachers refresher courses around the same time the policy was introduced, but which has not changed much in terms of the preparedness of science teachers to teach science.

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price